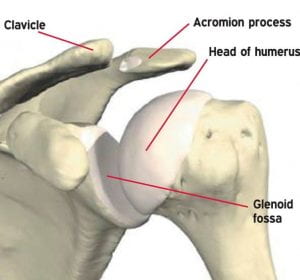

Shoulder dislocations are a common injury, especially among young athletes (Ahmed, 2019). It is stated to be the most frequently dislocated joint large joint in the human body (Mackenzie, 2013). Many consider this to be due to the anatomical structure, suggesting that the difference between the small glenoid cavity and the large humeral head makes this joint extremely susceptible to dislocation (Gaballah, Zeyada, Elgeidi, & Bressel, 2017). Shoulder dislocations can occur anteriorly, posteriorly and inferiorly, however anterior shoulder dislocations are by far the most common (Jones et al, 2019; Ahmed, 2019; Gaballah et al 2017). Inferior glenohumeral dislocations only account for approximately 0.5% of all shoulder dislocations (Plaga, Looby, Feldhaus, Kreutzmann & Babb, 2010). Posterior glenohumeral dislocations account for approximately 3% of all shoulder dislocations (Mackenzie, 2013). Whereas anterior glenohumeral dislocations account for approximately 95% of all shoulder dislocations (Olds, Ellis, Donaldson, Parmer & Kersten, 2015).

Shoulder dislocations are a common injury, especially among young athletes (Ahmed, 2019). It is stated to be the most frequently dislocated joint large joint in the human body (Mackenzie, 2013). Many consider this to be due to the anatomical structure, suggesting that the difference between the small glenoid cavity and the large humeral head makes this joint extremely susceptible to dislocation (Gaballah, Zeyada, Elgeidi, & Bressel, 2017). Shoulder dislocations can occur anteriorly, posteriorly and inferiorly, however anterior shoulder dislocations are by far the most common (Jones et al, 2019; Ahmed, 2019; Gaballah et al 2017). Inferior glenohumeral dislocations only account for approximately 0.5% of all shoulder dislocations (Plaga, Looby, Feldhaus, Kreutzmann & Babb, 2010). Posterior glenohumeral dislocations account for approximately 3% of all shoulder dislocations (Mackenzie, 2013). Whereas anterior glenohumeral dislocations account for approximately 95% of all shoulder dislocations (Olds, Ellis, Donaldson, Parmer & Kersten, 2015).

Primarily, one of the biggest risk factors for anterior, posterior and inferior shoulder dislocations is previous shoulder dislocations. Previous shoulder dislocations cause microtrauma to the structures within the glenohumeral joint. This can lead to a tear or erosion in the glenoid labrum during the force of the movement of the humeral head. This weakens the glenoid labrum and therefore weakens its attachment to the humeral head (Olds et al, 2015; Mackenzie, 2013; Plaga et al 2010; Eshoj et al 2020; Gallabah et al 2017).

Anterior (1), inferior (2) and posterior (3) dislocations.

Previous shoulder dislocations can also lead to muscle weakness and ligament laxity. Muscle weakness can occur due to a lack of exercise, and as recovering from a shoulder dislocation requires a significant period of rest, this can be expected following a shoulder dislocation. Yes, you would also be performing rehabilitation exercises. However, ultimately, to get your muscles back to significant strength, this can take a long time. Especially, when you are at extreme risk of re-dislocating your shoulder whilst your muscles are still weak, causing another long rest period, and in turn, even weaker muscles. Ligament laxity can occur following a shoulder dislocation due to overstretching during the forceful movement of the humeral head anteriorly, posteriorly or inferiorly (Olds et al, 2015; Mackenzie, 2013; Plaga et al 2010; Eshoj et al 2020; Gallabah et al 2017).

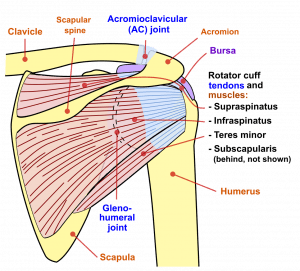

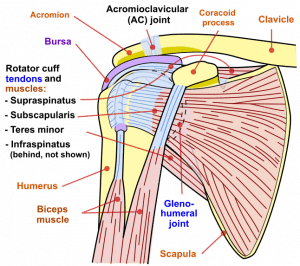

Muscles and ligaments of the glenohumeral joint play a huge role in the support and function of the shoulder. This includes: deltoids, pectoralis major and minor, biceps brachii, triceps brachii, coracobrachialis, latissimus dorsi, teres major and minor, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis, the capsular ligament and the glenohumeral ligaments (Biel, 2014). When these structures are weak or lax, it is harder for humeral head to sit in the joint, especially when subject to trauma (Olds et al, 2015; Mackenzie, 2013; Plaga et al 2010; Eshoj et al 2020; Gallabah et al 2017). This is especially supported for anterior shoulder dislocations as Eshoj et al (2020) and Gaballah et al (2017) both state the high risk of recurrent shoulder dislocations following their primary dislocation.

Muscles and ligaments of the glenohumeral joint play a huge role in the support and function of the shoulder. This includes: deltoids, pectoralis major and minor, biceps brachii, triceps brachii, coracobrachialis, latissimus dorsi, teres major and minor, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis, the capsular ligament and the glenohumeral ligaments (Biel, 2014). When these structures are weak or lax, it is harder for humeral head to sit in the joint, especially when subject to trauma (Olds et al, 2015; Mackenzie, 2013; Plaga et al 2010; Eshoj et al 2020; Gallabah et al 2017). This is especially supported for anterior shoulder dislocations as Eshoj et al (2020) and Gaballah et al (2017) both state the high risk of recurrent shoulder dislocations following their primary dislocation.

One of the greatest risk factors for inferior, posterior and anterior shoulder dislocations is collision sports. For instance, rugby and American football as well as combat sports, such as boxing, judo and karate (Jones et al 2019; Ahmed 2019).  For anterior shoulder dislocations, collision or positions in these sports can force the humeral head to separate from the glenohumeral joint, rupturing its attachment to the glenoid fossa. Often this will occur when the collision or position forces too much extension, abduction or external rotation of the shoulder beyond its physiological limits (Olds et al, 2015; Ahmed 2019).

For anterior shoulder dislocations, collision or positions in these sports can force the humeral head to separate from the glenohumeral joint, rupturing its attachment to the glenoid fossa. Often this will occur when the collision or position forces too much extension, abduction or external rotation of the shoulder beyond its physiological limits (Olds et al, 2015; Ahmed 2019).  For posterior shoulder dislocations, collision or positioning in these sports can force the humeral head to dislocate towards the back of the body. Often this will occur when the collision or position forces too much internal rotation with adduction beyond its physiological limits (Mackenzie, 2013; Ahmed 2019). For inferior shoulder dislocations, collision or positioning in these sports cause the humeral head against the acromion. Often this will occur when the collision or position forces too much abduction beyond its physiological limit (Plaga et al 2010; Ahmed 2019).

For posterior shoulder dislocations, collision or positioning in these sports can force the humeral head to dislocate towards the back of the body. Often this will occur when the collision or position forces too much internal rotation with adduction beyond its physiological limits (Mackenzie, 2013; Ahmed 2019). For inferior shoulder dislocations, collision or positioning in these sports cause the humeral head against the acromion. Often this will occur when the collision or position forces too much abduction beyond its physiological limit (Plaga et al 2010; Ahmed 2019).

Racket based sports are a risk factor for anterior and posterior shoulder dislocations.  For instance, badminton, squash and tennis (Jones et al 2019; Ahmed 2019). Racket based sports can result in your shoulder over stretching in a variety of movements beyond its physiological limits, particularly external rotation (creating a risk for anterior shoulder dislocations) as well as internal rotation with adduction (creating a risk for posterior shoulder dislocations) (Olds et al 2015; Mackenzie 2013; Ahmed 2019).

For instance, badminton, squash and tennis (Jones et al 2019; Ahmed 2019). Racket based sports can result in your shoulder over stretching in a variety of movements beyond its physiological limits, particularly external rotation (creating a risk for anterior shoulder dislocations) as well as internal rotation with adduction (creating a risk for posterior shoulder dislocations) (Olds et al 2015; Mackenzie 2013; Ahmed 2019).

Board based sports such as surfing and snowboarding, equestrian sports such as jumping and polo, and extreme sports such as rock climbing and skydiving are all risk factors for anterior, posterior and inferior shoulder dislocations (Jones et al 2019; Ahmed 2019).  For instance, falling off of these boards into a position of shoulder extension, abduction or external rotation beyond its physiological limits creates a risk of anterior shoulder dislocations (Olds et al 2015; Ahmed 2019). Falling off in a position of shoulder internal rotation and adduction beyond its physiological limits creates risk of posterior shoulder dislocations (Mackenzie 2013; Ahmed 2019). Or, falling off in a position of shoulder abduction beyond its physiological limits creates a risk of inferior shoulder dislocations (Plaga et al 2010; Ahmed 2019).

For instance, falling off of these boards into a position of shoulder extension, abduction or external rotation beyond its physiological limits creates a risk of anterior shoulder dislocations (Olds et al 2015; Ahmed 2019). Falling off in a position of shoulder internal rotation and adduction beyond its physiological limits creates risk of posterior shoulder dislocations (Mackenzie 2013; Ahmed 2019). Or, falling off in a position of shoulder abduction beyond its physiological limits creates a risk of inferior shoulder dislocations (Plaga et al 2010; Ahmed 2019).

Another risk factor for anterior and posterior shoulder dislocations is seizures and electric shocks (Olds et al, 2015; Mackenzie, 2013). During this, tiny muscle contractions can cause the humeral head to pull away from the glenohumeral joint, whether its anteriorly or posteriorly. Anterior shoulder dislocations are more likely to occur than posterior shoulder dislocations during a seizure or electric shock. However, without significant trauma, it is unlikely that a posterior shoulder dislocation will occur (Olds et al, 2015; Mackenzie, 2013).

Age and sex has been depicted by Olds et al (2015) to be a risk factor for anterior shoulder dislocations. This research suggests that people between the ages of 15-40 are at a higher risk of shoulder dislocations than those who are 40 and above, and that men are at a higher risk than women of shoulder dislocations.

Ultimately, research suggests that there are a multitude of different risk factors that can contribute to anterior, posterior and inferior shoulder dislocations. Previous shoulder dislocations, collision sports, combat sports, racket sports, board based sports, seizures, electric shocks, age and sex are all significant factors to be considered when determining risk factors for shoulder dislocations.

References

Gaballah, A., Zeyada, M., Elgeidi, A., & Bressel, E. (2017). Six-week physical rehabilitation protocol for anterior shoulder dislocation in athletes. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, 13(3), 353-358.

Ahmed, H. (2019). A Rehabilitation Protocol For Athletes Diagnosed With Shoulder Dislocation. Physical Education, Sport and Kinetotherapy Journal, 56 (2), 32-37.

Jones, G., Wilson, E., Hardy, M., Summers, D., Edwards, J., & Munro, M. (2019). BMA Guide to Sport Injuries: The Essential Step-by-Step Guide to Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment. London: Dorling Kindersley Limited.

Plaga, B., Looby, P., Fledhaus, S., Kreutzmann, K & Babb, A. (2010). Axillary Artery Injury Secondary to Inferior Shoulder Dislocation. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, (39) 5, 599-601.

Olds, M., Ellis, R., Donaldson, K., Parmar, P & Kersten, P. (2015). Risk factors which predispose first-time traumatic anterior shoulder dislocations to recurrent instability in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med, (49), 913-923.

Mackenzie, D. (2013). Point-of-care Ultrasound Facilitates Diagnosing a Posterior Shoulder Dislocation. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, (44) 5, 976-978.

Biel, A. (2014). Trail Guide to the Body: a hands on guide to locating muscles, bones and more. USA: Books of Discovery.

Eshoj, H., Rasmussen, S., Frich, L., Hvass, I., Christensen, R., & Boyle, E. et al. (2020). Neuromuscular Exercises Improve Shoulder Function More Than Standard Care Exercises in Patients With a Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Dislocation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Orthopaedic Journal Of Sports Medicine, 8(1), 1-12.