Running total of hours: 142

Within this session, I was able to work with returning patients. I enjoy their follow up appointments and their progress interests me a great deal. I feel as though I do not always provide the patient with an effective enough program and do not yet have the confidence in my own ability to correctly prescribe the right volume and intensity of exercises. I understand that much of the time, treatments can be adapted and varied, depending on progress and that trial and error is often an effective means, providing I have adequately and comprehensively reflected on my practice and learnt from any errors. It is not always possible, however to develop an ongoing plan of which can be adapted each session, as the nature of the clinic and the individuals seen do not always allow for follow up appointments. When working with athletes, for example, it is in their best interests to maintain a longer term, continued plan, not only to help reduce pain but to help reduce further risk of injury. With nonathletes and general members of the public however, I have found that often they are satisfied when slight progress is made and as long as their pain subsides and if they are reassured by a diagnosis, then they do not tend to always return.

Patient 1 – Follow up for insertional achillies tendinopathy

Patient Overview:

Although this patient felt really positive about her previous treatment and noticed considerable change in her symptoms straight afterwards and later on as a result of her exercise prescription, her initial symptoms had returned two days prior to this session and were of similar severity; a sharp pain in her posterior aspect of her heel, most likely the insertion site of the achillies tendon and also around her medial malleolus. Other symptoms, such as the stiffness and feeling of ‘wooden feet’ in the mornings also returned so I felt as though the patient was back at square one with her injury and with no obvious explanation as to why this may have happened, I was left rather confused.

Although the treatment plan on the patients notes on Cliniko suggested a follow up appointment consisting of further sports massage and progression of exercises to facilitate her return to running, because no real progress was made, I decided to conduct another thorough assessment to be sure that my initial diagnosis was still feasible.

From her subjective and objective assessments, it became clear that the tenderness was

more apparent in her tibialis posterior and the patient was adamant that this was exactly the same as her previous treatment, however from the notes and my memory of the session, there was no recollection of this. I did not question the patient and accepted that it will remain unclear as to whether this was a new symptom or not, however it would be reasonable to assume that this irritation of the tibialis posterior may be due to her excellent adherence to her arch strengthening exercises for the treatment of pes planus.

I was unsure as to whether this was a symptom which would be expected or not but was reassured by my supervisor that this pain may start to decrease over time and that we did not have to modify her exercises in the meantime. The tibialis posterior was the cause of the patient’s pain this week and as such it was recommended that STM be performed. When treating this injury in previous appointments, the advice that I was given by my supervisor was to avoid administering any treatment that may irritate the inflamed tendon, instead allow for freer motion and build strength in the associated musculature; addressing the ‘tightness’ in the calf felt by the patient and most likely restricting ankle movements and subsequently creating friction of the structures.

However, on this occasion I had a difference supervisor who advised that I should perform firm deep tissue massage and soft tissue release over the most painful site of pain, with rationale being to desensitise the area to help reduce pain.

I have since tried to find supporting evidence to support this treatment. Although Bowring & Chockalingam (2010) suggested deep tissue massage for tibialis tendinitis, the study also noted that there was no real evidence in support of this for the reduction of pain or increase in function and strength but merely supported theoretical potential for the breaking down of scar tissue and the facilitation of tissue healing. A more recent review by Joseph, Taft, Moskwa and Denegar (2012) which, although some evidence existed on some effectiveness of deep friction massage, the researchers struggled to make a conclusion from their findings. Much of the research was not conducted using deep friction massage as the only treatment modality and so it was suggested that further research was needed in order to test this method alone.

Two years later, Loew et al. (2014) did just that and attempted to test the originally derived theory by Cyriax of deep friction massage treatment for tendinitis, having tested the method on two separate studies consisting of 40 participants with lateral elbow tendinitis and 17 participants with iliotibial band friction syndrome. Of the two studies, neither injuries showed deep friction massage to be effective and although the number of participants in the study was not large, with no significant differences and previous lack of evidence in support of this treatment, I have struggled to find sufficient rationale behind this method.

Conversely, and more specifically, in the case of tibialis posterior tendinosis, a review by Bowring & Chockalingam (2010) recommended rest as a potential treatment for acute tendinopathy as well as the use of orthotics and exercises. At the acute stage, stretching of the gastrocnemius and soleus would aid in increasing dorsiflexion when indicated, however it was suggested that strengthening of the tibialis posterior and should be given when the acute inflammation has subsided.

This could be where this treatment is limiting progression. Because in my objective assessment I found the patient to exhibit pes planus, I wondered whether this may have contributed to the achillies pain, so I prescribed arch strengthening exercises, however this is contraindicated by this review in the early stages of tibialis posterior dysfunction. Whether this pain had only just started to occur from the incorporation of strengthening exercises, or whether it was here from the beginning, it may be advised to stop this exercise for the foreseeable weeks until the inflammation has subsided. The heel raises that I prescribed to help increase eccentric and concentric strength of the achillies tendon and subsequent pain reduction would also activate the tibialis posterior and so this may explain why this caused further irritation to the patient; I will look to reduce these from her exercise routine until the inflammation has subsided also (Bowring & Chockalingam, 2010).

Although strengthening of arch support muscles such as the tibialis posterior and strengthening and stretching of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles was recommended (Lee & Choi, 2016; Ridge et al., 2018), it may be advisable to wait until the acute swelling and inflammation has subsided and so a period of immobilisation and then controlled mobilisations to increase range of motion may be a more sensible and staged progression in this instance (Bowring & Chockalingam, 2010).

During this treatment, and as advised, I performed two modalities in order to achieve the same outcome. Both of which I tested for effectiveness.

The aim of the treatment was to increase range of motion in the ankle joint, reducing any stiffness and potential friction on the tendons, specifically the achillies and tibialis posterior tendons and surrounding soft tissue. To address the possible joint involvement indicated by the feeling of wooden feet, stiffness and pain in the joints in the mornings, mobilisations with movement was performed to increase dorsiflexion of the ankle joint. There is an abundance of research published, supporting the positive effects on mobilisations with movements for increasing ankle dorsiflexion and reducing pain in individuals with lateral ankle injuries (Loudon, Reiman, Sylvain, 2014; Nisha, Megha and Paresh, 2014) and in knowing that there is also evidence to suggest that limited dorsiflexion can alter running kinematics (Mason-Mackay, Whatman and Reid, 2017), this is a modality worth considering.

To address the possible soft tissue involvement indicated by the feeling of tightness in the patient’s lower posterior legs, soft tissue massage was performed to lengthen the triceps surae muscle group (Stefansson, Brandsson, Langberg and Arnason, 2019).

In order to test which treatment was more effective, we used the knee to wall test, as previously found to be effective as a clinical measure for ankle dorsiflexion and mobility (Hoch & McKeon, 2011; O’Shea & Grafton, 2013).

After the mobilisations with movement, precisely 3 sets of 60seconds, testing in between each set, the patient’s range of movement increased by a third. I then performed the soft tissue release of the tibialis posterior and deep tissue massage of the triceps surae, only to find a reduction in range of motion, most likely due to the irritation of the inflamed tendons and possibly the patient’s apprehension in performing the test due to the increase in pain intensity. This lead to the conclusion that mobilisations with movement was the most effective treatment in this instance and these findings were therefore reflected in her notes, suggesting mobilisations only for a follow up appointment.

However, I am led to question the original rationale behind administering the deep tissue massage and soft tissue release over the painful area, as this was supposed to reduce pain sensitivity in the area but instead, pain levels increased during treatment.

Also, I later noted that after the patient’s previous appointment, improvements in pain and function were reported but that the pain only returned two weeks later, suggesting that the treatment was effective and so It will be of great value to me in my learning to find out whether the more hands on treatment working directly on the inflamed tendon is more effective long term, even if not on during the treatment.

I do understand, however that I have added two variables to the rehabilitation, deep tissue massage directly over the tibialis posterior and insertion area of achillies, as well as mobilisations. If the patient reports improvements in her next session, I will be unlikely to be able to differentiate between the two treatments.

Patient 2 – Unfortunately, my second patient did not arrive and this was the second session that he missed. I was made aware of the traffic delays in the city, so hope that his was a factor but had hoped that basic politeness would result in a courtesy call of apology.

I have noticed that over the past month, the clinic has experienced a number of cancellations at the last minute, giving little or no chance for the therapists to arrange for alternative appointments. It is within the clinic policy for the patient to provide notification of a cancellation at least six hours in advance. I am sympathetic to the fact that there are some occasions that are unavoidable and that sometimes any notification is impossible or that sometimes mistakes happen and that appointments get forgotten. In these occasions, businesses have to accept the loss of income or wasted time. However as this seems to be becoming a common occurrence, it may be useful to make alterations to the policy. It has been suggested that although there is no set time of which patients should notify cancelations, if no-shows are common then any increases in policy time could serve to reduce those instances (Huang & Zuniga, 2014).

As a group of five students without patients in this hour of the session, we all gathered around together to debate and discuss efficacy of soft tissue massage and it’s role within the clinic environment or sports therapy and rehabilitation. I have reasonably strong opinions on the psychosocial benefits of massage in any form, as often made obvious within this blog, regardless of the physiological aspects of this treatment and was able to provide some references for this, which will serve me well when discussing this area of treatment with patients in the future.

I found this type of ‘debate’ environment very useful, as it mimicked how I would imagine a discussion would develop on this type of subject with a patient or another health care professional, who perhaps needs extra understanding on our role as sports therapists or on our treatment rationale.

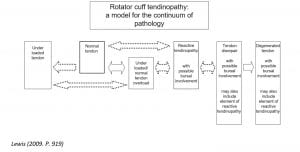

Free hour between patients – I used this time to catch up on my notes from my previous session and was able to join another student sports therapist who was conducting an initial appointment for shoulder pathology. This is an area that I find challenging, so I was happy to work together with another student to help diagnose this patient with possible rotator cuff tendinopathy and offer my skills in developing an effective strengthening program, which is something that I do feel confident doing.

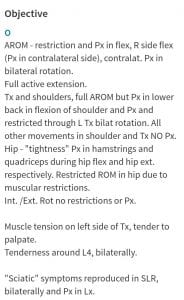

Patient 3 – 13 year old rugby player, pain in thoracic spine, specifically on palpating T2.

This was another patient under the age of 16 who attended the clinic with his parent. I felt a little more comfortable treating this patient, having experienced treating a child the day before, however, fortunately on this occasion, the parent sat in waiting room and left the patient to be assessed by himself. I felt much more natural speaking with the patient on a one-on-one environment as opposed to balancing the conversation between myself, parent and child and felt as though the patient could open up more to me without the judgement or interruptions from his parent.

The patient was experiencing upper thoracic pain and on palpation, we established that it was on the spinous process of T2 specifically. This pain was noticed since a heavy weekend of playing and now occurs during physical activity and sometimes at rest. After seeing his team physiotherapist, who the patient reports as too busy to see for the foreseeable, he was assured that it was tight muscles and was advised to visit a sports therapist for a soft tissue massage.

However, although I wanted to oblige to his request of a soft tissue massage, I wanted to be sure that there was no underlying issue that could be contributing to his pain rather than just treating the symptoms. I conducted an assessment, with the patient’s permission. Initially, I did not find a reason for the pain and was confused as to why the most painful palpable area was on the spinous process.

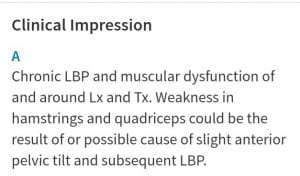

Baffled, I requested the assistance of the clinic supervisor who, on entering the cubicle immediately spotted his hyper lordotic seated posture, of which was the most pronounced that I had ever seen. I was very surprised that this had not occurred to me and that I had not noticed this, especially as I had recently attended an informative lecture on posture and shoulder/thoracic pain. I can only think that the reason this was missed, is because the patient was so young and that not only my observational skills and common sense were clearly lacking in this assessment, but that I had unconscious predisposed misconceptions that poor posture is developed over time and not present in children so young. Now that I know the possible benefits of considering alterations in posture when addressing shoulder and thoracic pain, I would be doing my patients huge injustices if I made this incorrect assumption regarding the younger individuals; correcting poor posture early on could prove paramount in future risk factors for injury, serving to prevent muscle imbalances, skeletal deformities and developmental dysfunctions, with early poor posture habits contributing to future deterioration and musckoloskeletal strain (Kim, Cho, Park and Yang, 2015).

One of the most useful exercises I learnt from the aforementioned shoulder lecture was the method of asking a patient to place their finger on their sternum then using their chest to push those fingers away as a means to inadvertently correct their shoulder posture. I found this incredibly useful in helping my young patient acquire a method to remind himself of the posture that he would be aiming to achieve through re-education and strengthening; just one motion created the desired effect and with the need to adjust technical language for younger patients to understand, this was a very useful tool.

I was also able to use other information acquired from the shoulder lecture regarding hyper kyphosis as this was the first part of the shoulder symptom modification procedure (Lewis, 2009; Lewis, 2011). I found this video by the Physio tutors very helpful in understanding this procedure: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sYTW7u6ZoCI.

As modifying this patient’s thoracic spine by way of reducing the kyphotic curve, reduced his symptoms, according to this procedure, this indicated the need to focus on strengthening the thoracic spine and as such, I looked to prescribe some of these newly learnt techniques to help reduce this. I prescribed a posterior capsule stretch, as recommended by Lewis (2009) and attempted to recommend strengthening. Although I have a wide range of mobility exercises for the thoracic spine of which I was able to show the patient, including the lawn mower and threading the needle, I only had one exercise on building muscular strength for the back muscles; the low row specifically targeting the rhomboids and lower and middle traps. It is especially important that I develop and repertoire of exercises, especially ones that require no specialist equipment, for patients who do not have access to a gym to use a row machine.

I found an excellent video demonstrating a good exercise that can be done at home and one I feel more comfortable prescribing in the future.

References –

Bowring, B., & Chockalingam, N. (2010). Conservative treatment of tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction-A review. Foot. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foot.2009.11.001

Hoch, M. C., & McKeon, P. O. (2011). Normative range of weight-bearing lunge test performance asymmetry in healthy adults. Manual Therapy, 16(5), 516–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2011.02.012

Huang, Y. L., & Zuniga, P. (2014). Effective cancellation policy to reduce the negative impact of patient no-show. Journal of the Operational Research Society. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2013.1

Joseph, M. F., Taft, K., Moskwa, M., & Denegar, C. R. (2012). Deep friction massage to treat tendinopathy: A systematic review of a classic treatment in the face of a new paradigm of understanding. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.21.4.343

Kim, D., Cho, M., Park, Y., & Yang, Y. (2015). Effect of an exercise program for posture correction on musculoskeletal pain. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 27(6), 1791–1794. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.27.1791

Lee, D., & Choi, J. (2016). The Effects of Foot Intrinsic Muscle and Tibialis Posterior Strengthening Exercise on Plantar Pressure and Dynamic Balance in Adults Flexible Pes Planus. Physical Therapy Korea, 23(4), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.12674/ptk.2016.23.4.027

Lewis, J. S. (2009). Rotator cuff tendinopathy/subacromial impingement syndrome: Is it time for a new method of assessment? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(4), 259–264. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2008.052183

Lewis, J. S. (2011). Shoulder Symptom Modification Procedure ( SSMP ) V2 Date : Symptomatic movement or posture 1 : Symptomatic movement or posture 2 : (1), 2011.

Loew, L. M., Brosseau, L., Tugwell, P., Wells, G. A., Welch, V., Shea, B., … Rahman, P. (2014). Deep transverse friction massage for treating lateral elbow or lateral knee tendinitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003528.pub2

Loudon, J. K., Reiman, M. P., & Sylvain, J. (2014). The efficacy of manual joint mobilisation/manipulation in treatment of lateral ankle sprains: A systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(5), 365–370. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092763

Mason-Mackay, A. R., Whatman, C., & Reid, D. (2017). The effect of reduced ankle dorsiflexion on lower extremity mechanics during landing: A systematic review. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 20(5), 451–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2015.06.006

Nisha, K., Megha, N. A., & Paresh, P. (2014) Efficacy of weight bearing distal tibiofibular joint mobilization with movement (MWM) in improving pain, dorsiflexion range and function in patients with post acute lateral ankle sprain quick response code. Int j physiother res.

O’Shea, S., & Grafton, K. (2013). The intra and inter-rater reliability of a modified weight-bearing lunge measure of ankle dorsiflexion. Manual Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2012.08.007

Ridge, S., Henderson, A., Bruening, D., Jurgensmeier, K., Olsen, M., Griffin, D., … Davis, I. (2018). Midfoot Angle Changes During Running After an 8-week Foot Strengthening Program. Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics, 3(3), 2473011418S0040. https://doi.org/10.1177/2473011418s00405

Stefansson, S. H., Brandsson, S., Langberg, H., & Arnason, A. (2019). Using Pressure Massage for Achilles Tendinopathy: A Single-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing a Novel Treatment Versus an Eccentric Exercise Protocol. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 7(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967119834284