Monday 6th September 2021 – Monday 8th November

Hours: 6 (2 e-learns, 1 x webinar 2 x virtual classrooms)

Reflection Model

- Gibbs Reflective Cycle 1988

What Happened?

- Programme structure explained:

- 2 x 1 hour supervised weekly sessions. 30. mins education followed by 30 minutes of exercise

- Programme is for any kind of joint pain e.g. autoimmune, degenerative, fibromyalgia, gout, etc.

- Data collection and system training

- Conversation Facilitation Training and Exercise Selection

- Developing skills on how to facilitate a group conversation

- Exercise progressions and regressions

What were you thinking and feeling?

- During the training process there was only 1 synchronous training session which was the conversation facilitation training and exercise selection. Other training was asynchronous but needed to be completed before hand. I found it a bit strange that we didn’t really spend much time 0n the synchronous sessions understanding joint pain; however, on reflection the asynchronous sessions were comprehensive and the expectation is if you are electing to work on the programme you will complete the pre-requisites.

- The conversation facilitation training was interesting as we had to engage in a conversation, guided by a facilitator, and make note of what tactics they were employing. After a couple of these conversations we were then paired up and facilitated a conversation ourselves. I was fairly nervous for this; however, the session was about building up your skills so all criticism, if any, was constructive.

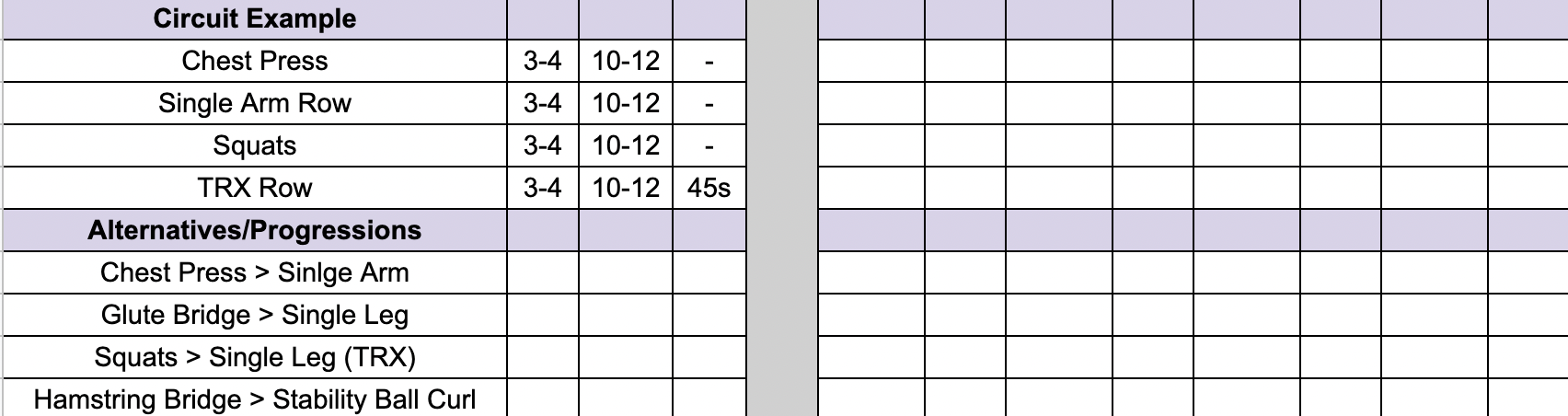

- The exercise selection was quite an easy component of the programme. For example, we were asked how we may progress and regress a sit to stand.

- Leg Extension – Regression

- Sit to Stand – Exercise

- Squat (Supported or Unsupported) – Progression

- Lunge – Progression

What was good and bad about the experience?

- I think the conversation facilitation training was really beneficial for my practice as even though I have experience of delivering group rehab, this programme requires an educational component in a group setting. Normally, I would be coaching a group rehab class and then spend time with patients of a 1-1 basis for the educational components of the programme. Therefore, it was important to have the skills to guide the conversation and help individuals within the group feel comfortable in contributing to the discussions.

- There wasn’t anything particularly bad about the experience. I would have preferred more synchronous sessions as I find bouncing ideas off colleagues around me really valuable for my practice. However, with the current climate, working from home is advisable and in terms of the programme resources should be focused on the ‘pinch points.’ In other words, we could have spent hours talking about joint pain, how to manage it, how it impacts people, etc. However, if we are unable to effectively guide and facilitate a discussion then the conversations may veer off track, people may become disengaged and the atmosphere may not become conducive to a safe learning and exercise environment. Therefore, it wouldn’t matter how much ‘expertise’ we had on the topic of joint pain as those looking to benefit from that expertise may not be able to due to a facilitators lack of skill.

Analysis

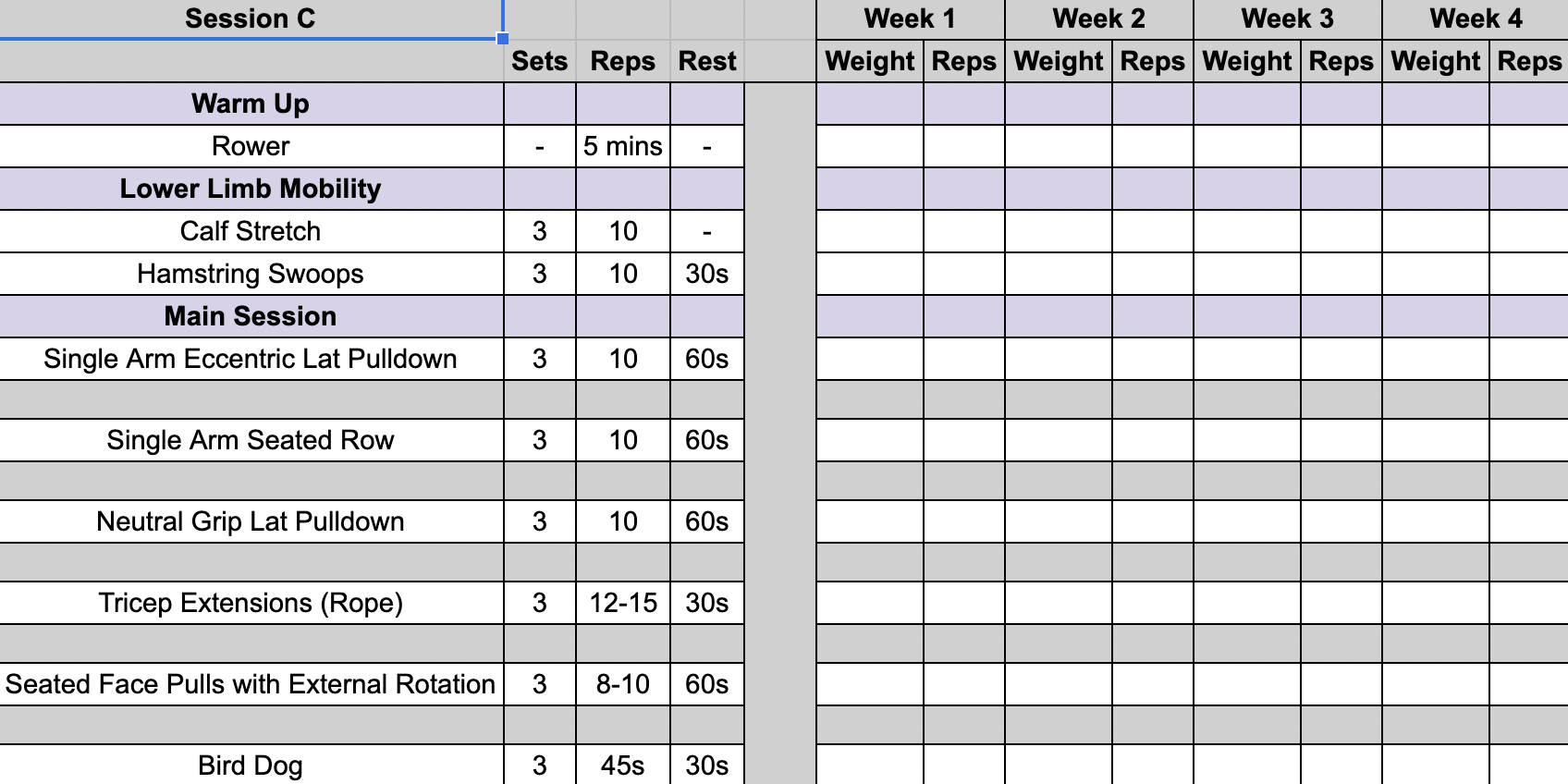

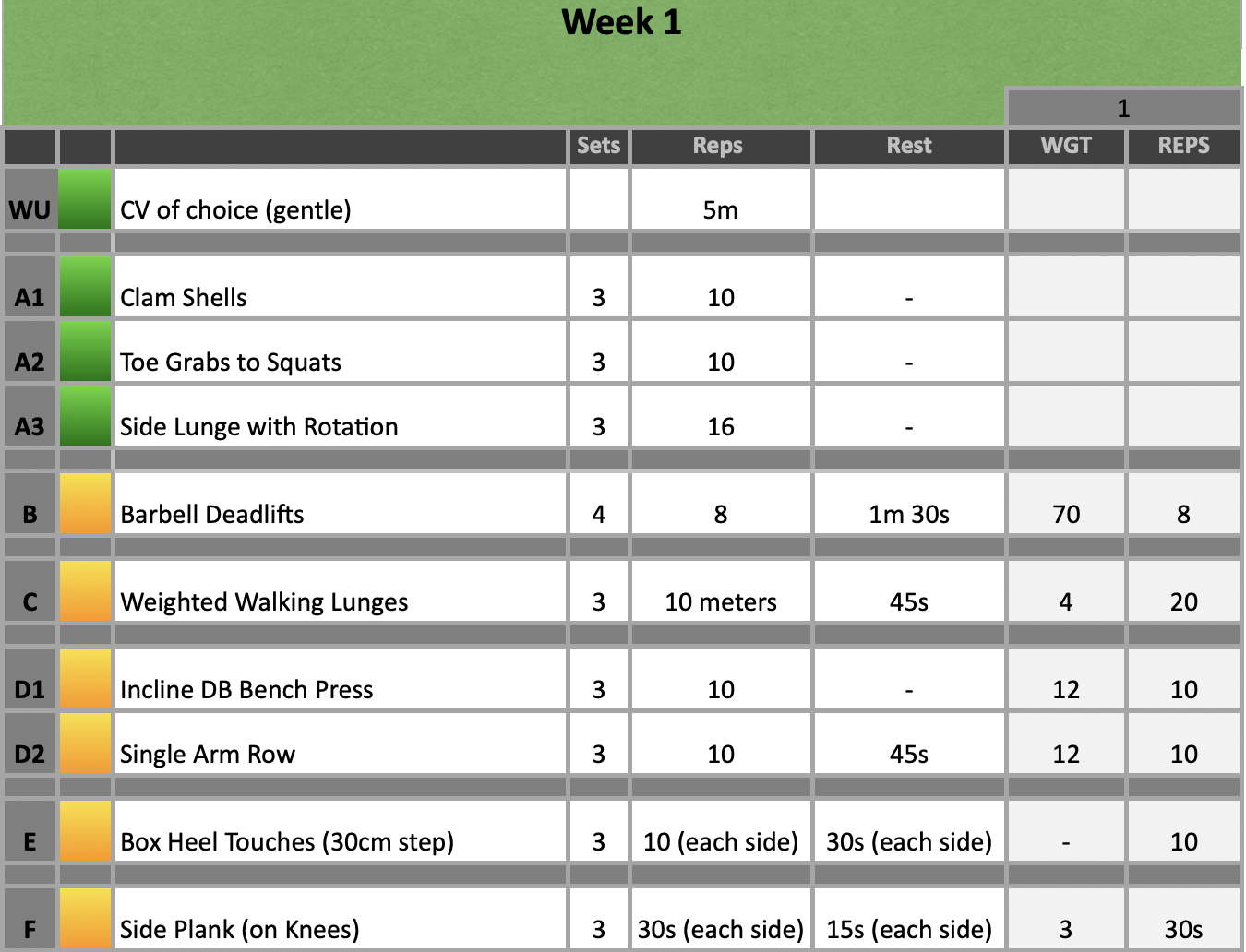

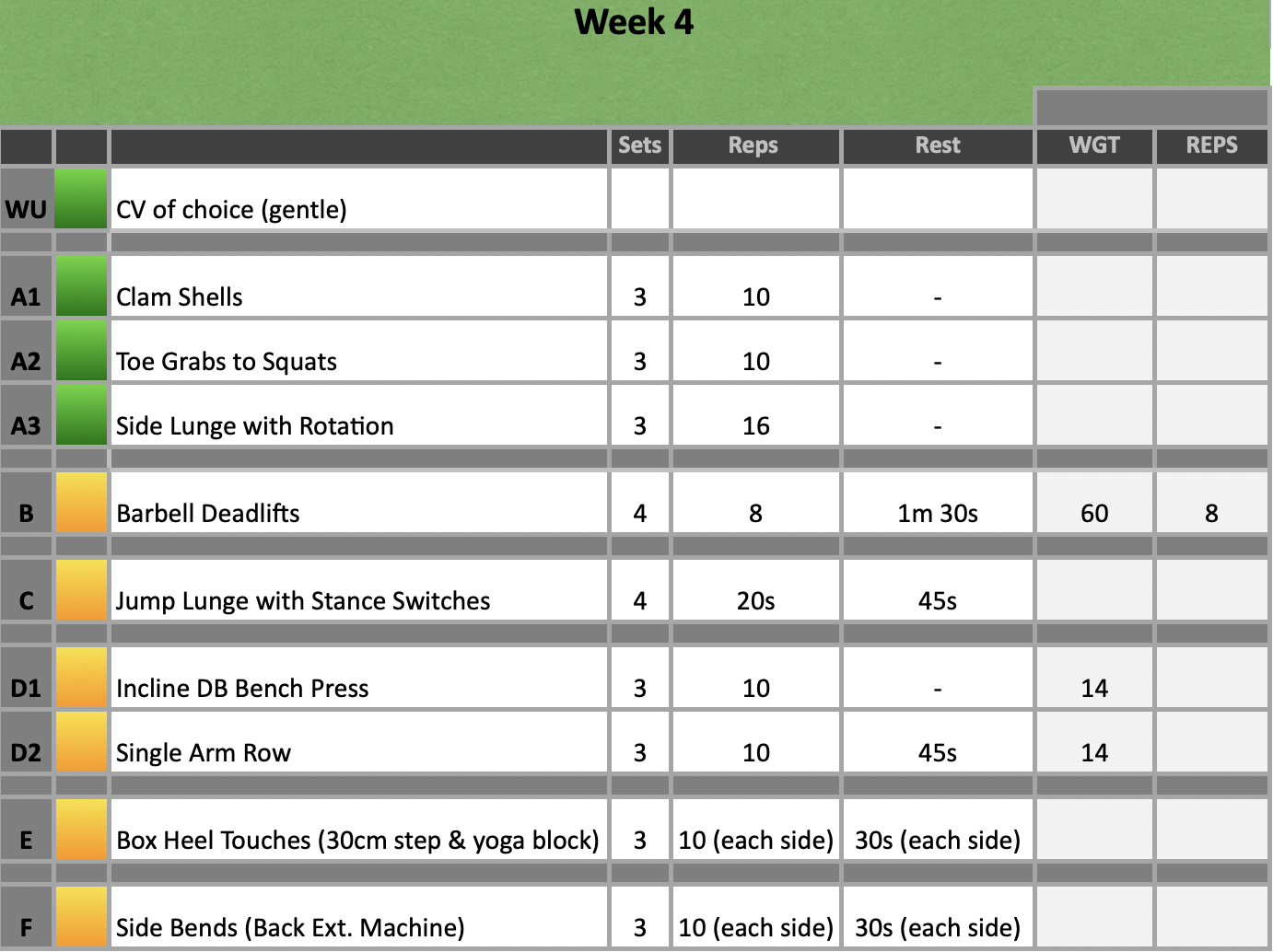

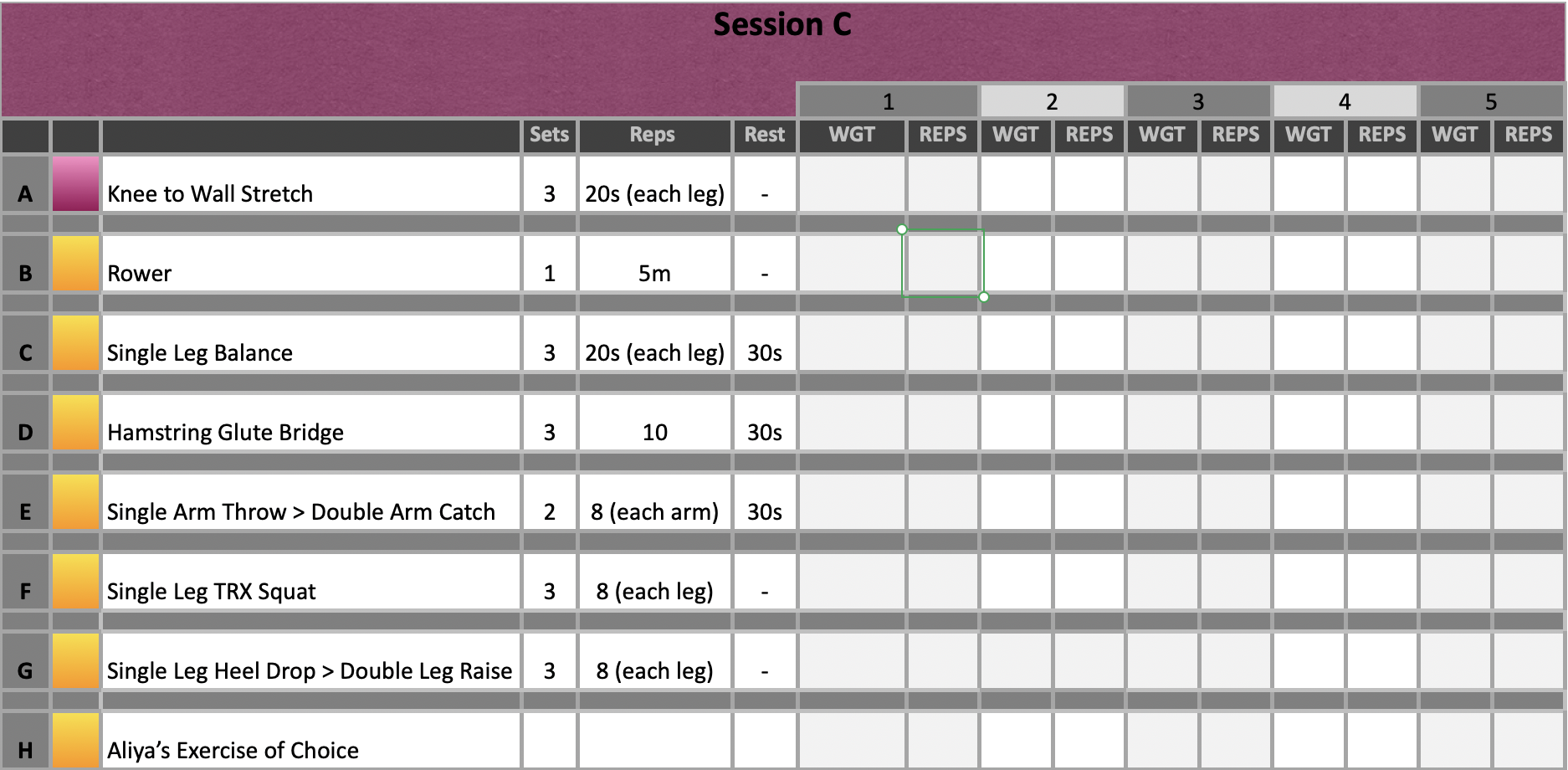

- Although comfortable with exercise selection, it was beneficial to have a discussion around this – specifically concerning joint pain. For example, in one group you may have someone waiting for a hip replacement, another with widespread pain and another with chronic lower back pain (CLBP). Therefore, it was beneficial to cement the idea that the progressions and regressions aren’t just for monitor patient progress but also for an effective and all-inclusive exercise class.

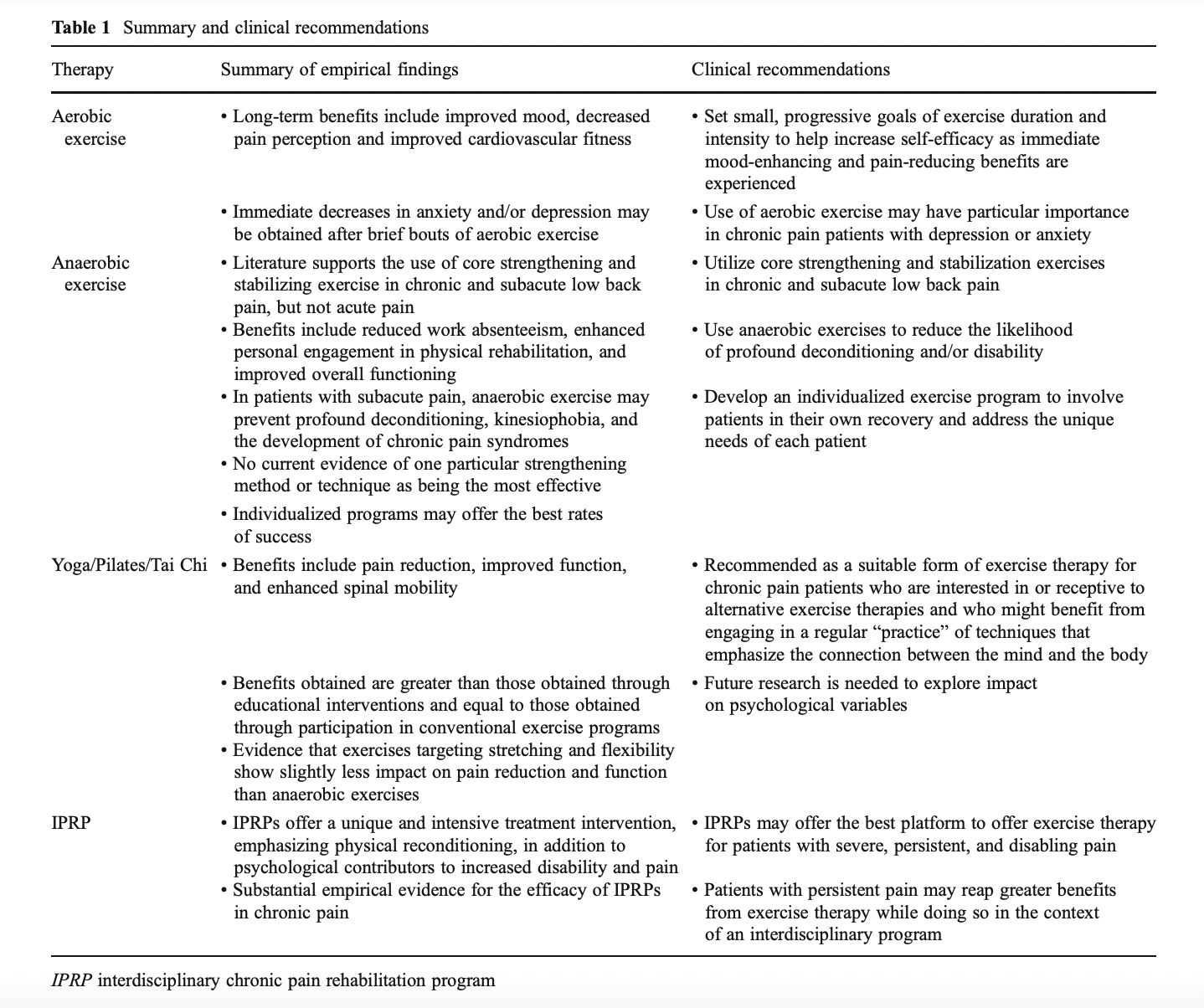

- The table below was taken from a paper by Sullivan, et al. (2012) and highlights some of the ways exercise can be a useful tool in the rehabilitation of patients with chronic pain. For example, exercise can release endorphins and assist in weight loss, both of which have been associated with a reduction in joint pain. Therefore, being able to adapt exercises for individuals within a group is key for them adhering to this programme and hopefully benefiting from the exercise. For example, if exercises were not regressed appropriately some may find the challenge too great or painful which may result in demotivation of consolidation on the belief that movement or exercise makes their joint pain work.

Conclusion

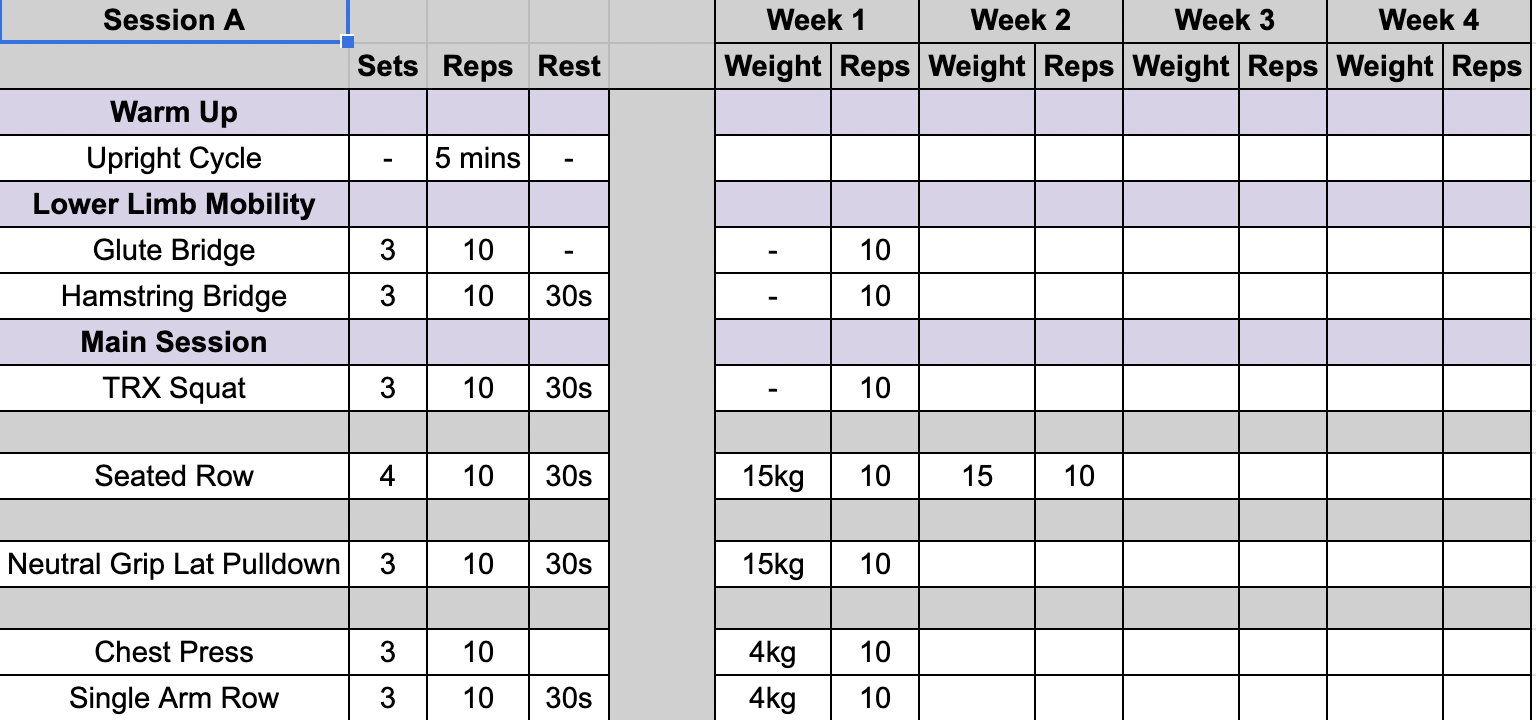

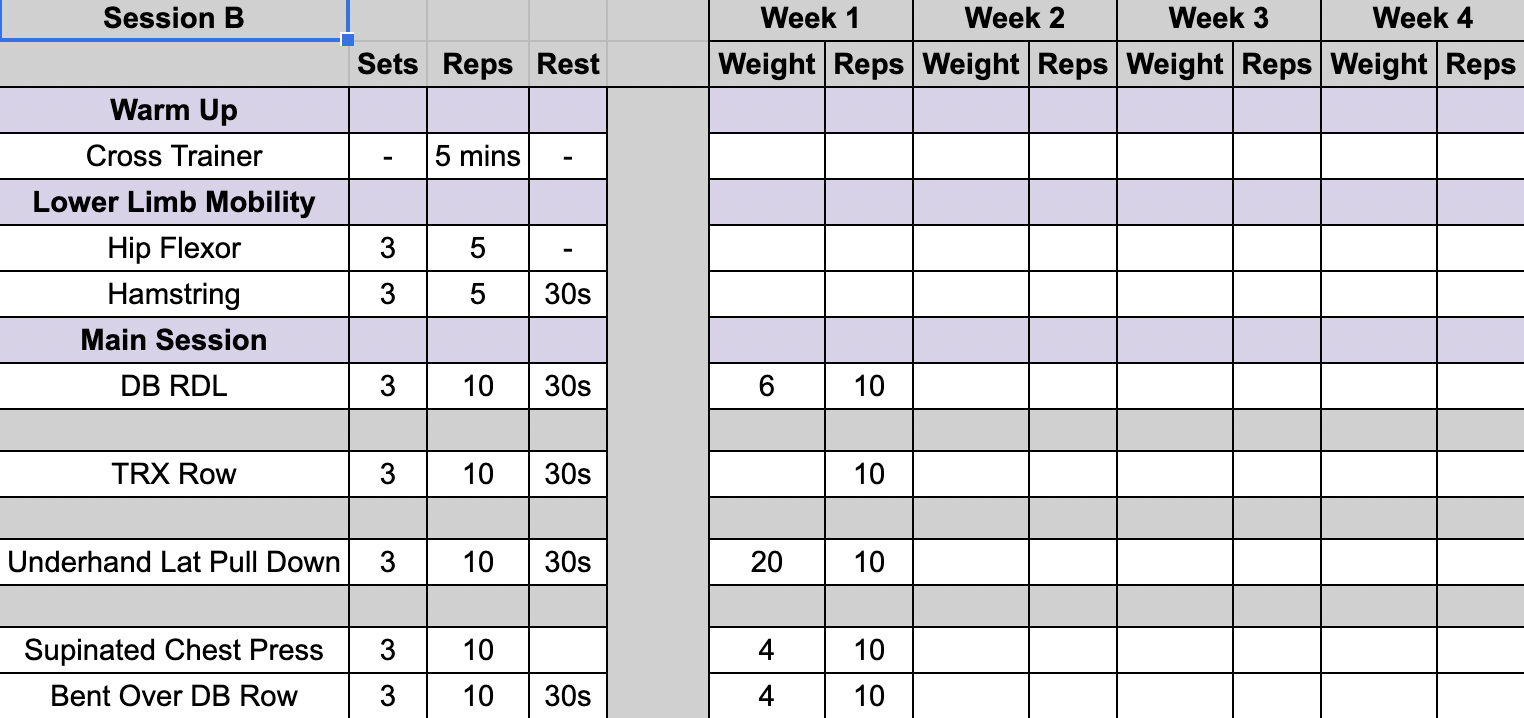

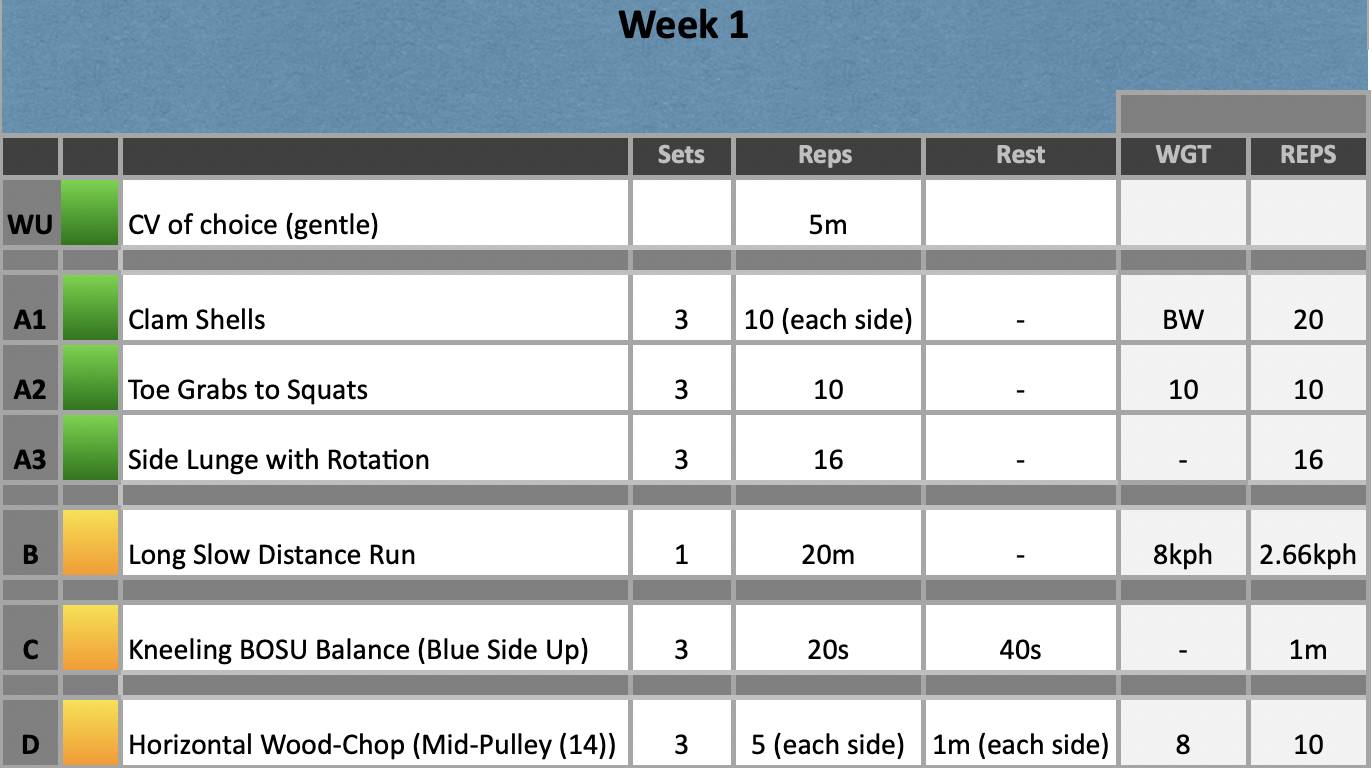

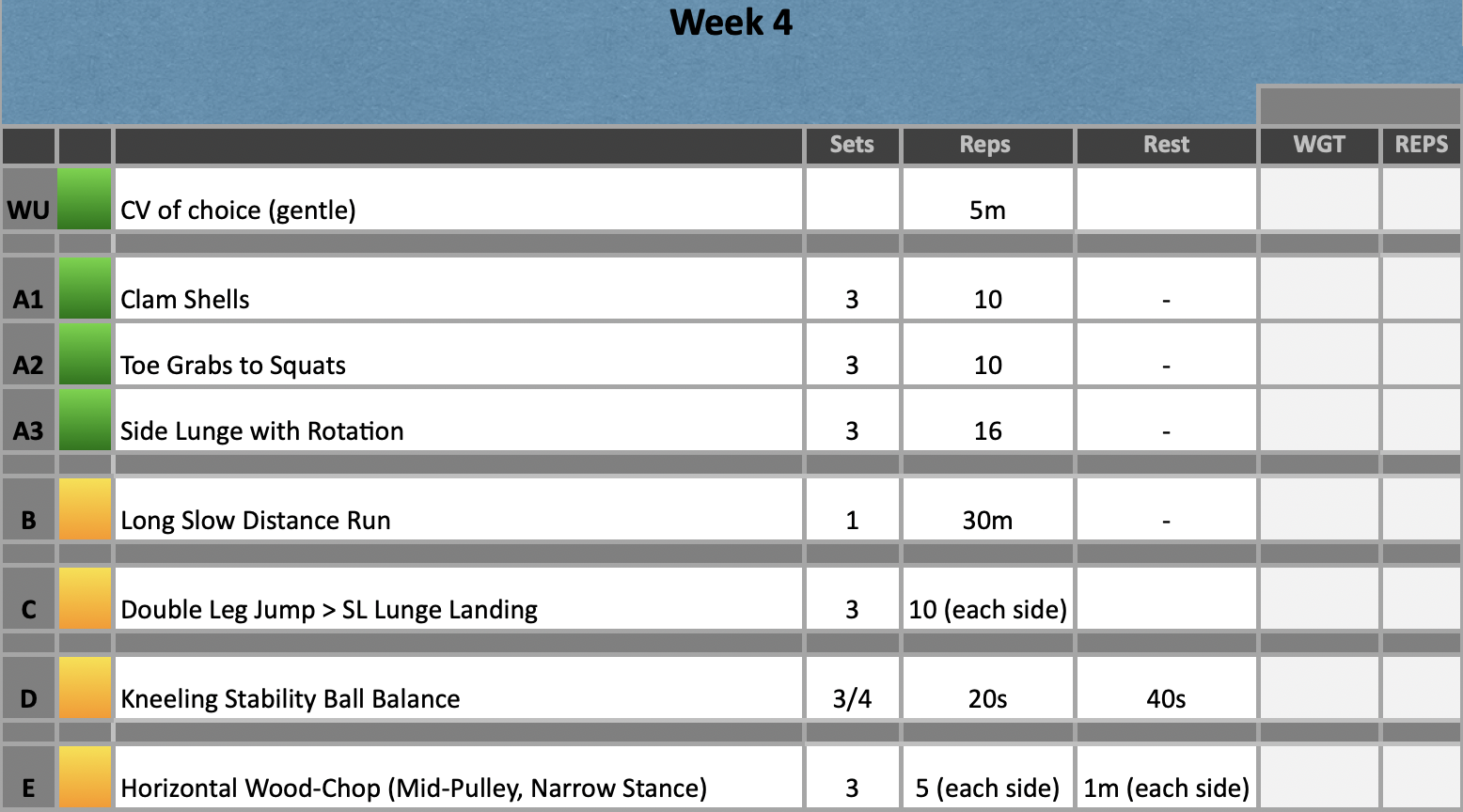

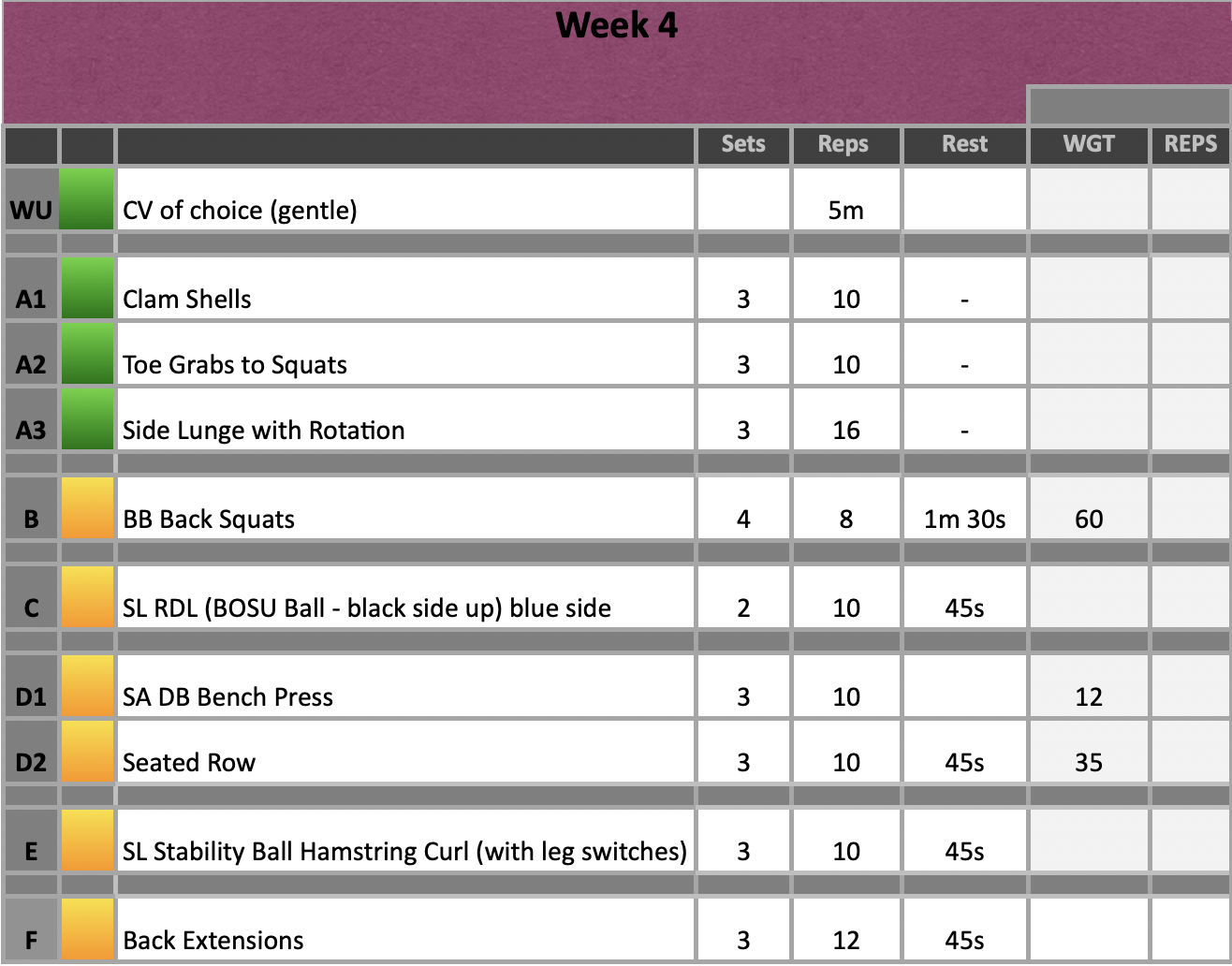

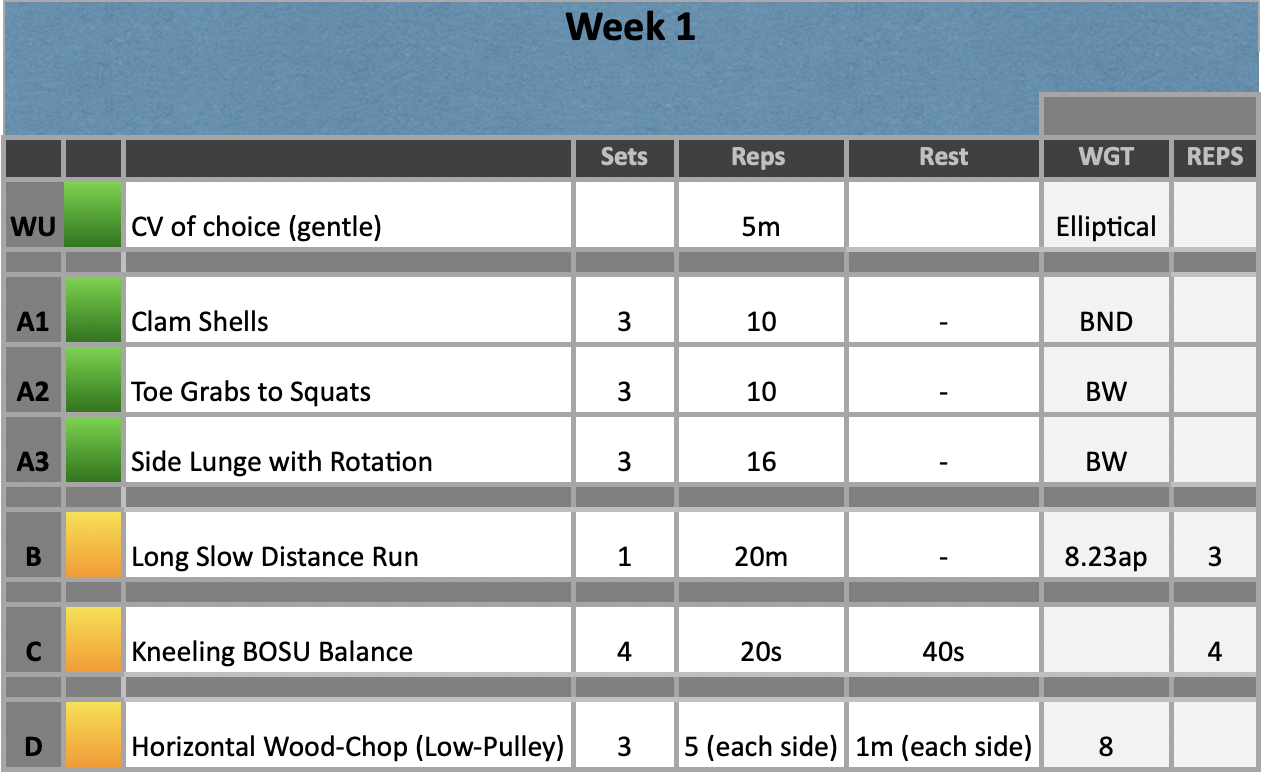

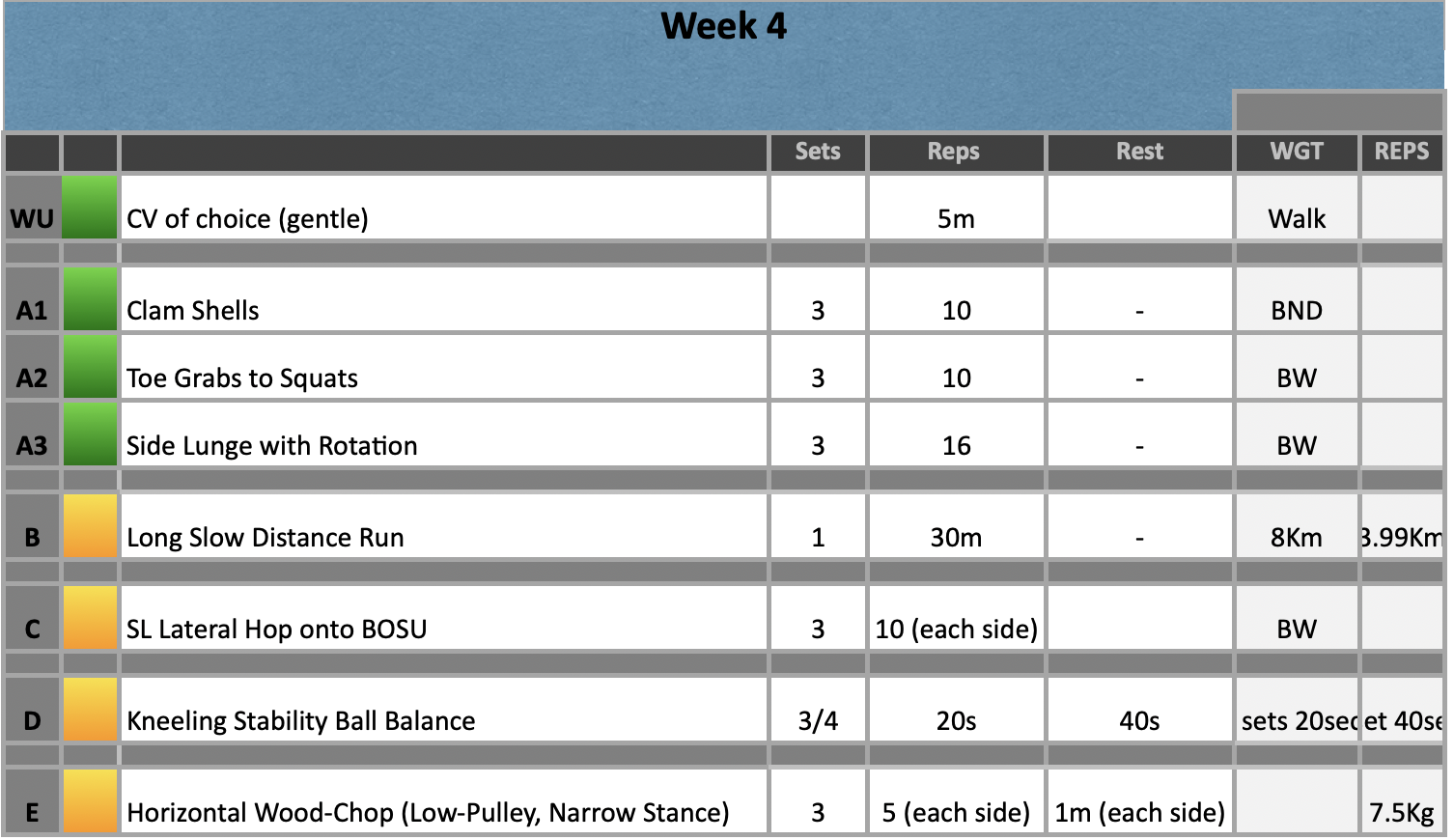

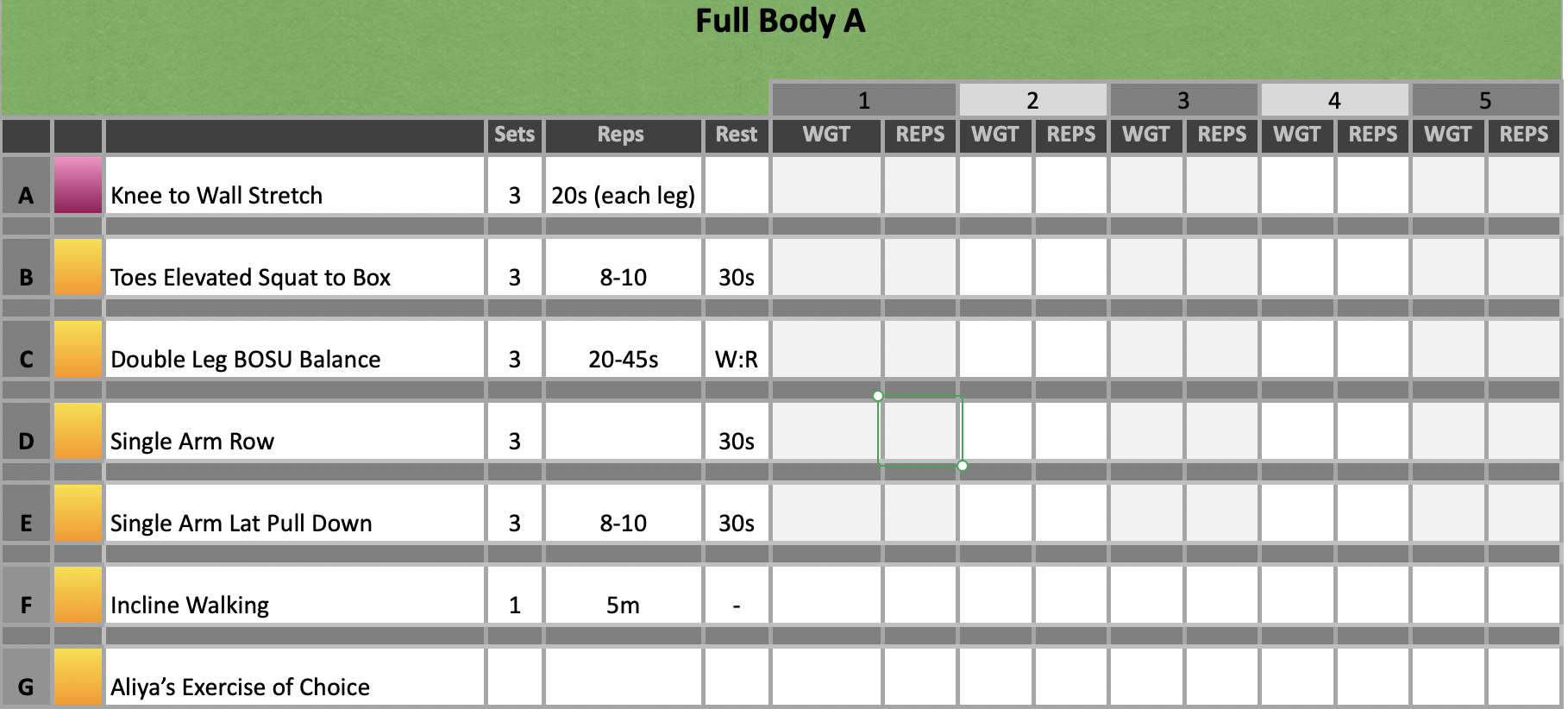

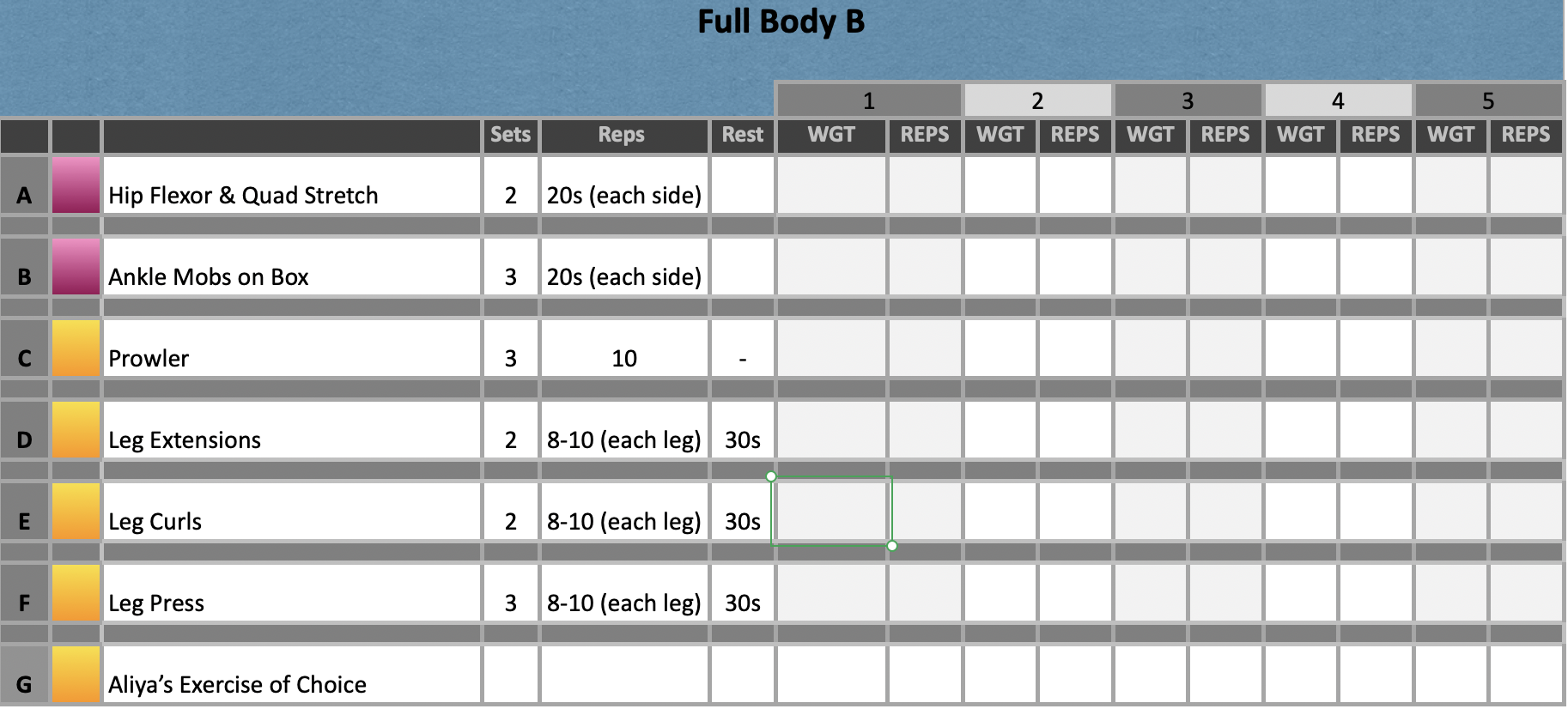

- I start delivering on the joint pain programme 24th January 2022. Therefore, I will spend time working on facilitation skills that we have been taught but also building a 12-week programme with suitable progressions and regressions as these two factors are fundamental to the success of the programme.

Revisiting Reflection

References

- Sullivan, A. B., Scheman, J., Venesy, D., & Davin, S. (2012). The role of exercise and types of exercise in the rehabilitation of chronic pain: specific or nonspecific benefits. Current pain and headache reports, 16(2), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-012-0245-3

What Happened?

What Happened?