February 14th February 2022 – March 7th March 2022

Hours: 12 (12 x 1 hour sessions over 4 weeks – 3 sessions per week)

Patient presentations:

- Traumatic L1 burst fracture 2021 after a motorcross accident – conservatively managed.

-

Patient complaining of stiffness in the back and a pins and needle type discomfort from lower back into glutes which he calls sciatica.

- Patient was no longer under the care of the hospital and his physio was happy for him to resume gym-based exercise.

- The patient does not seem to have any movement restrictions except for extension of the thoracic spine. I don’t know what his ROM was previously; however, the patient has limited thoracic extension. In addition to this there is a lot of apprehension with certain movements, e.g. RDL’s.

- Patient reports being around 80% back to normal and would like a gym programme to help him get as close to 100% as normal. Main concern he would like to address = lower back stiffness & reduce pins and needles sensation.

Reflection Model

- Gibbs Reflective Cycle 1988

Exercise Prescription

3 supervised sessions a week – the patient does not complete any unsupervised sessions in the gym or at home.

What Happened?

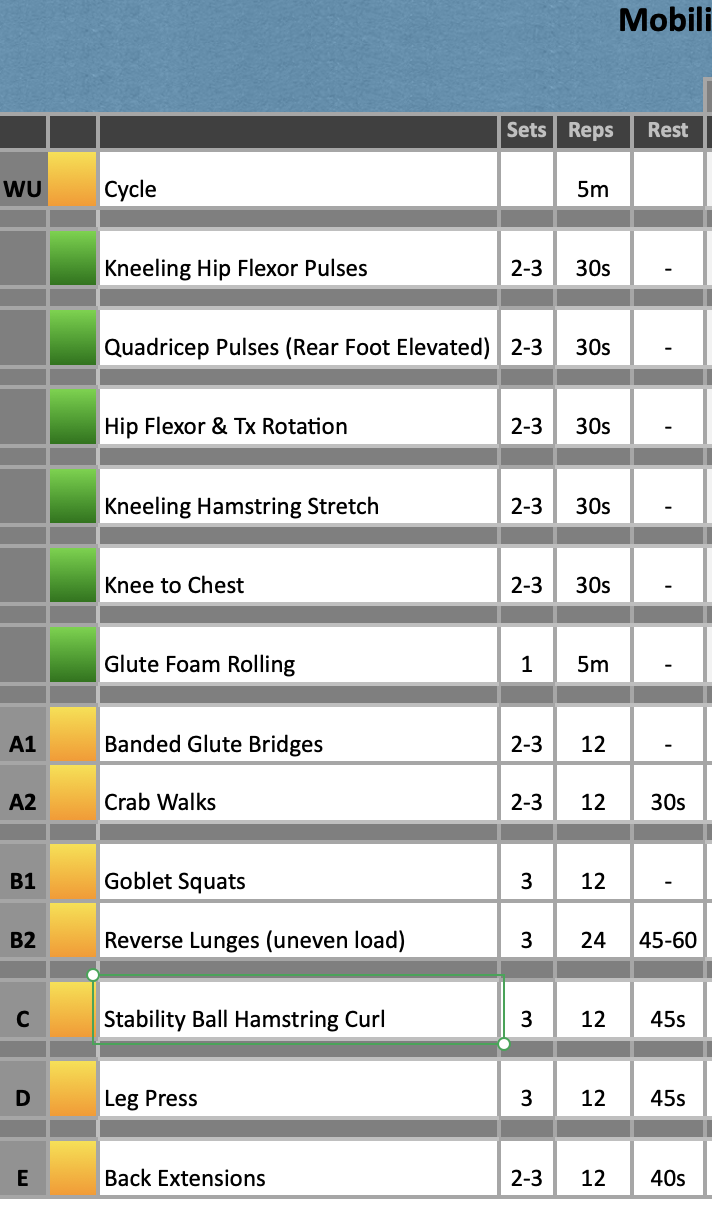

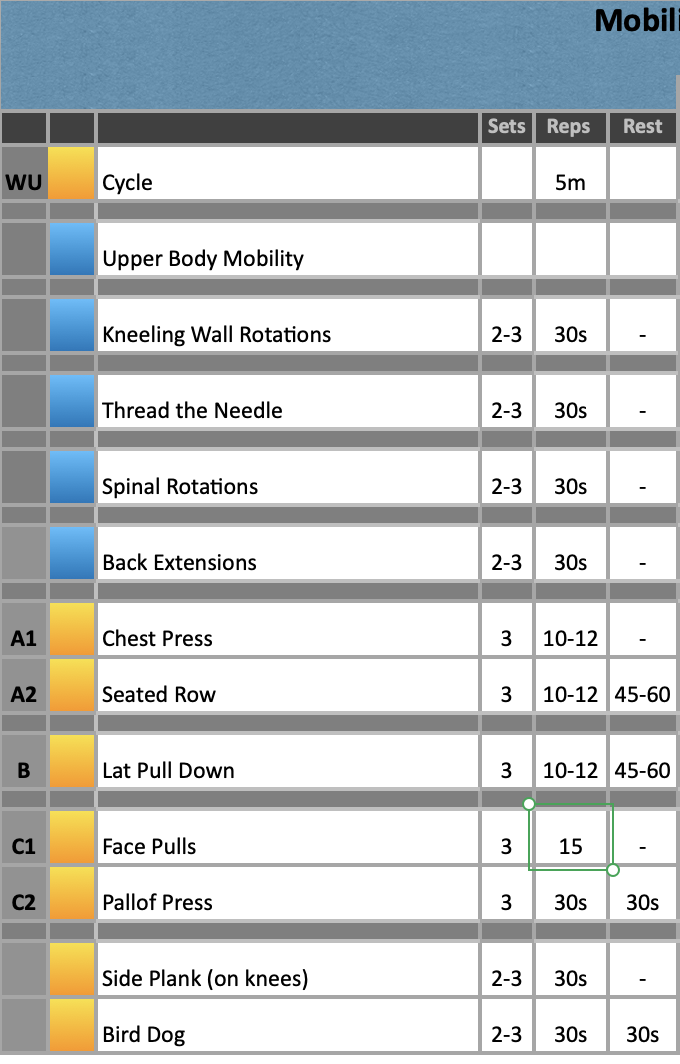

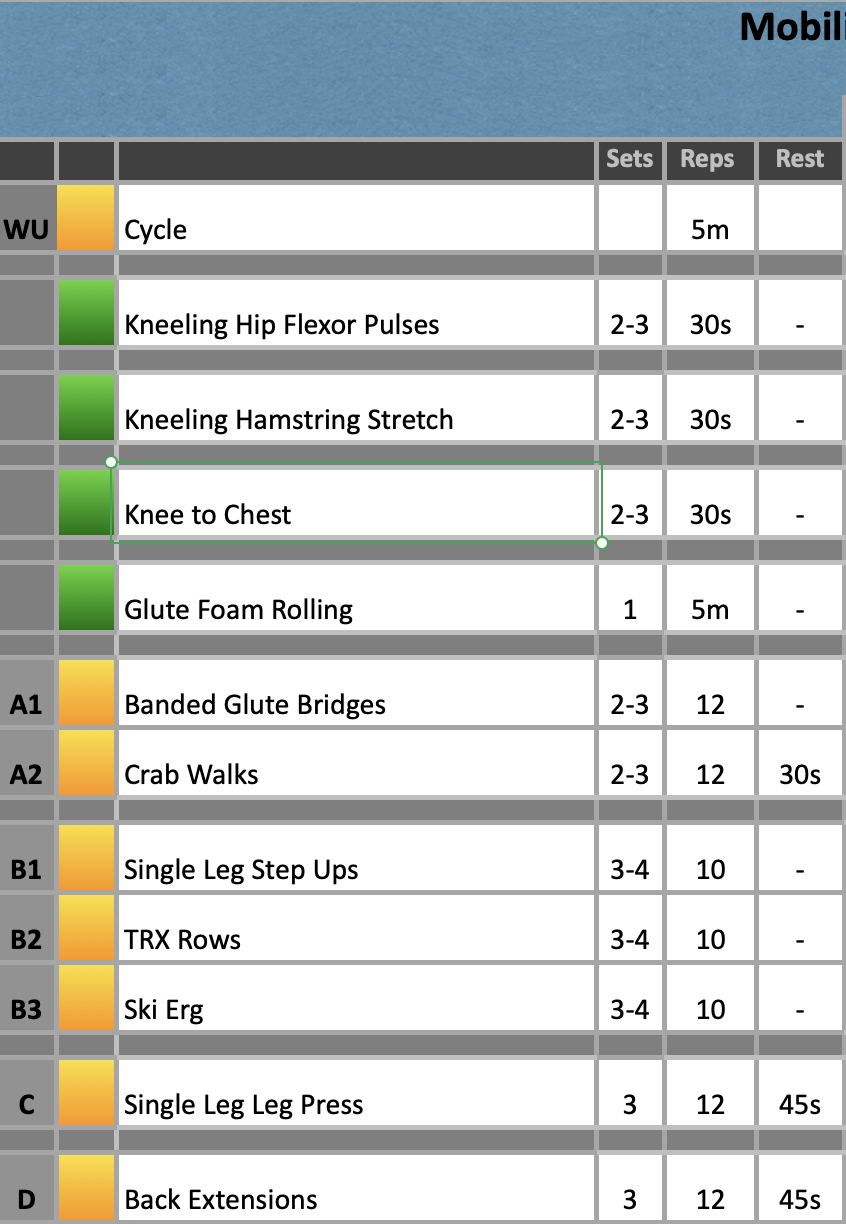

- Half of the 1 hour sessions were dedicated to mobility and the rest consisted of S&C and/or cardiovascular training. Resistance training and mobility focused on the lower limb and back.

- Upper body mobility – Back extensions/Cobras were a replacement for cat camels as this patient could not perform this movement.

- It proved very difficult to activate the patients glutes – banded glute bridges, single leg glute bridges, banded lateral walks and clam shells all failed to generate any glute activation. In the end, a hip abduction machine provided some glute med activation so this replaced banded glute bridges; however, sometimes the patient would feel his legs working rather than his glutes on the hip abduction machine.

- There are a lot of exercises that I had to encourage the participant to complete due to apprehension. For example, when instructed on how to use the back extension machine his initial response was, ‘ I can’t do that – no way.’ After spending time explaining the benefits of the movement for lower back strength and that he can cease the exercise if he feels uncomfortable he was then happy to proceed.

- By the end of the 12 sessions, the patient was reporting reduced stiffness in his back but it was short lived, i.e., if he didn’t have a session for 3-4 days he would feel like he starts to stiffen up again. His pins and needles had reduced in intensity and frequency; however rotational movements still seem to be an aggravating factor for this symptom.

What were you thinking and feeling?

- The patient was relatively sedentary outside of his gym session so I was concerned about how much impact the sessions would make. He stated that he doesn’t have time to come into the gym by himself and would rather have someone help and support him when he is in training. I think this may be way the reduction in his back stiffness is short lived as he wasn’t completing any additional mobility exercises at home (although he was encouraged to do so) and remaining sat down for a significant period of time each day.

- Initially, I was unsure on what the conservative management would be for this type of injury and did some research of physical therapy management. However, my reading highlighted that exercises such as bridging, back extensions and bird dog are all suitable for strengthening and stabilising the lumbar spine – an important area to address in this type of injury (find evidence)

- I felt quite frustrated that I could not successfully or consistently get the patients glutes to activate. I tried all the exercises I could think of but it is still something we are struggling to get right.

Analysis & Evaluation

- Evidence suggests that thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurological deficits can be successfully treated through a non-surgical approach. (Pehlivanoglu, et al., 2020; Sahoo, et al. 2022). Therefore, I was confident that this patient was suitable in addition to both their doctor and physiotherapist approving an exercise training programme.

- I found it really challenging to find research that provides an evidence base approach to end-stage rehabilitation of a traumatic thoracolumbar burst fracture. Therefore, I treated how the patient presented and what I knew would need to be addressed. For example, a fracture will impact stability of the spinal column; therefore, it was really important for me to work on stability of the lumbar spine with exercises such as back extensions and side planks.

- The patients apprehension to complete certain exercises was concerning and may indicate a psychological barrier to rehabilitation success. However, it is good that he trusts me enough to try the exercises before completely ruling them out. So, I am hopeful over time he will become increasingly confident and take on more complex movement patterns or tasks with less hesitation.

- Being unable to activate the glutes means that cannot be effectively strengthened.

-

The ability to actively control the muscles of the hip plays an important part in lumbar segmental stability. As a function of the gluteus maximus muscle, the sacroiliac joint delivers loads from the trunk to the lower limb, and if this joint moves excessively, it results in pressure on the joints and disks between the L5–S1 vertebral body, sacroiliac joint, and pubic symphysis, which leads to functional failure of the sacroiliac joint and low back pain. (Jeong, et al. p.3814 2015)

- I need to investigate further into why this patient cannot activate his glutes. Jeong, et al, 2015, found that glute strengthening alongside lumbar stabilisation exercises improved lower back pain. Therefore, proper strengthening of the glutes may be key for long-term back health in my patient.

- He does have difficultly crossing his leg over when performing glute foam rolling and cannot cross his legs in general. He reports a sensation of restriction whilst pointing to his TFL (sometimes his ITB) and this could be inhibiting the glutes from firing correctly.

-

- Despite, encouragement the patient doesn’t appear to be intrinsically motivated as he will not perform any exercises on his own or at home. I will need to see if this is something we can work on as he is sedentary and movement could help reduce the sensation of stiffness. He also reports that when he sits for too long that he experiences a pins and needle sensation like sciatica from his back to his glutes; therefore, there could potentially be a disc bulge irritating the nerves. Completing a small amount of exercise at home or even taken active breaks from sitting may help speed up his recovery but also reduce discomfort.

Conclusion

- Next phase needs to incorporate strengthening in rotational movement patterns. The patient reports that when he twists he experiences the pins and needles sensation. This programme has very little rotational movement patterns so incorporating this into the programme may help to strengthen this movement pattern and reduce symptoms

- I also need to address inhibition of the gluteals – being sat down for significant portions of the day is not going to be helpful so in addition to finding more exercises to help target the glutes, I need to consider how to reduce TFL activation and encourage the participant to move more outside of his sessions.

Revisiting Reflection

References

- Jeong, U. C., Sim, J. H., Kim, C. Y., Hwang-Bo, G., & Nam, C. W. (2015). The effects of gluteus muscle strengthening exercise and lumbar stabilization exercise on lumbar muscle strength and balance in chronic low back pain patients. Journal of physical therapy science, 27(12), 3813–3816. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.27.3813

- Pehlivanoglu, T., Akgul, T., Bayram, S., Meric, E., Ozdemir, M., Korkmaz, M., & Sar, C. (2020). Conservative Versus Operative Treatment of Stable Thoracolumbar Burst Fractures in Neurologically Intact Patients: Is There Any Difference Regarding the Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes?. Spine, 45(7), 452–458. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003295

- Sahoo, M., Ray, S., Mahato, P., & Sahoo, U., & Panigrahi, T. (2020). Outcome of nonoperative management of thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurological deficits – An analysis. Journal of Orthopedics, Traumatology and Rehabilitation. 12. 79. 10.4103/jotr.jotr_2_20.