January 2022 – March 2022

Hours: 10

Patient decided to continue with rehabilitation and completed a further 10 hours at 2 x 45 minutes session per week.

Patient presentation:

- 10 year old girl with right hemiplegia

- She has a leg length discrepancy due to excessive tone in her calves which causes tip-toe walking.

- Parents want to focus on stretching the calf complex, strengthening the right lower limb and increasing adherence to exercises.

- The patient wants to improve core and upper limb strength.

- Her right upper limb is weak – she has poor grip strength and inhibited motor skills

- The upper limb in currently not a focus at the patient has had botox and all stakeholders want to capitalise on its effects.

Reflection Model

- Gibbs Reflective Cycle 1988

Exercise Prescription

What Happened?

- Since the previous training block the patient and her parents decided that more sessions would prove beneficial. They also asked if slightly longer and more frequent sessions would be beneficial. This where I had the opportunity to emphasise my want to drive repetition learning to improve neuroplasticity. In my previous reflection, I mentioned that this was a concern of mine and I wanted to try and get the patient to do more exercises at home. As this was proving difficult, it was agreed that increasing to 2 sessions per week at 45 minutes per session would be a good compromise in the interim.

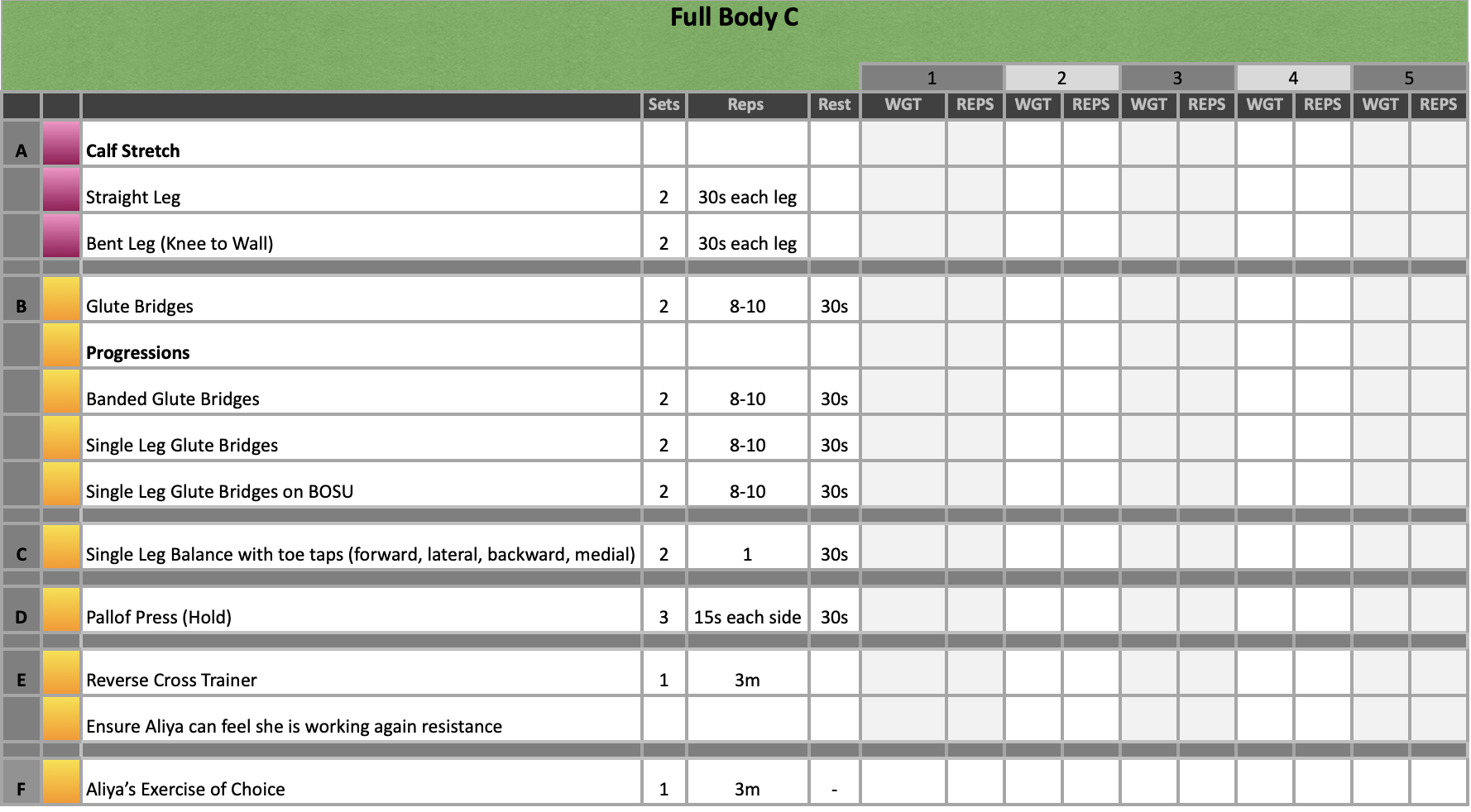

- There was a significant difference in the patients calf complex since she was last in for sessions. She had botox over Christmas and as a result her ROM had significantly improved. Her parents really wanted to capitalise on this window of opportunity and continue stretching the calf whilst is was more ‘pliable.’ There was a real focus on wanting to keep this as functional as possible. For example, the patient has poor eccentric strength and control when walking down steps and she was generally just struggling to complete the movement. She noted that walking downstair without immediately going onto her tip toes was painful. Similarly, there was a focus on trying to address muscular control when sitting down. The patient tends to get to a certain degree of knee and hip flexion and then has no control for the remainder of the lowering phase.

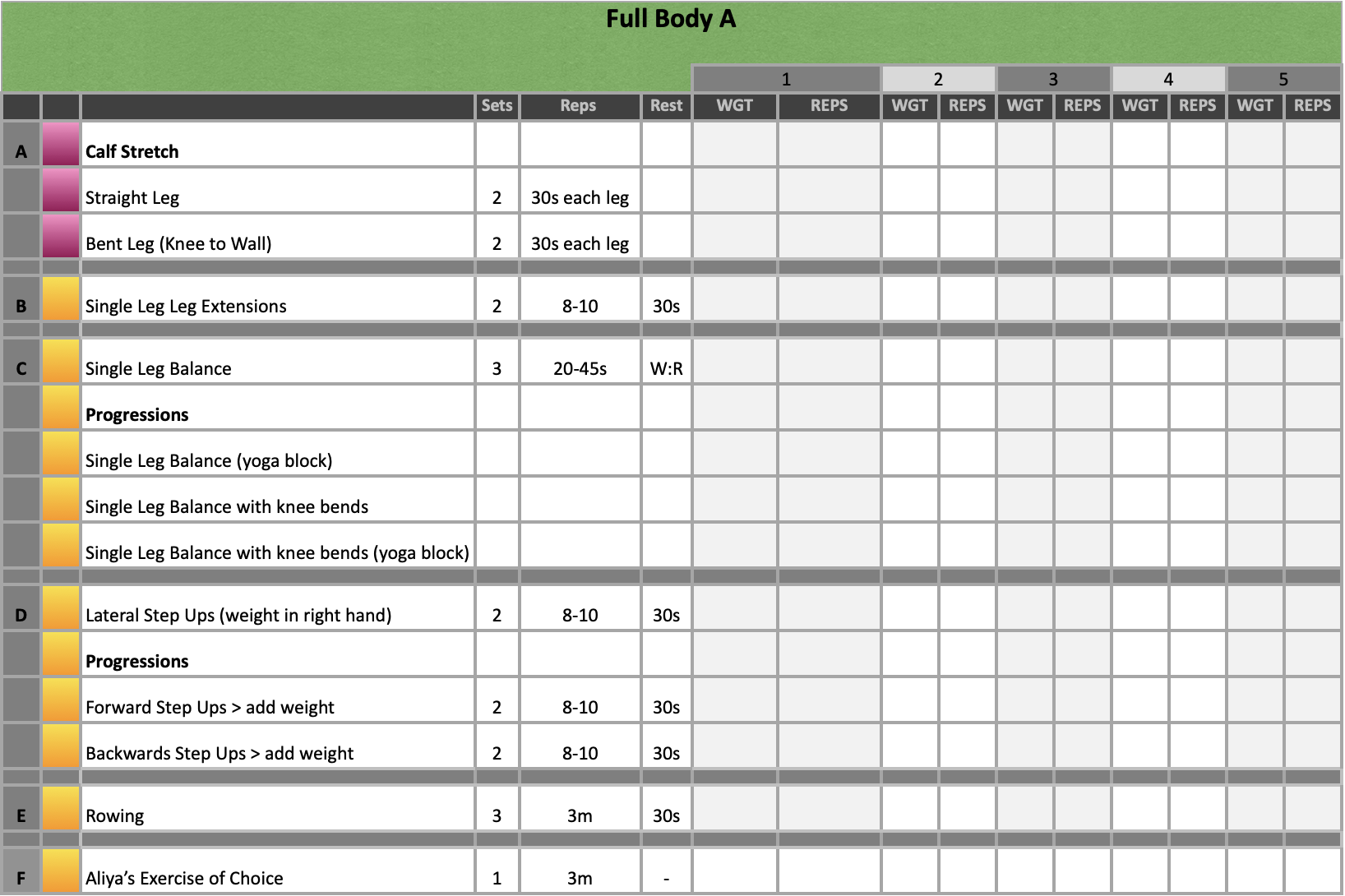

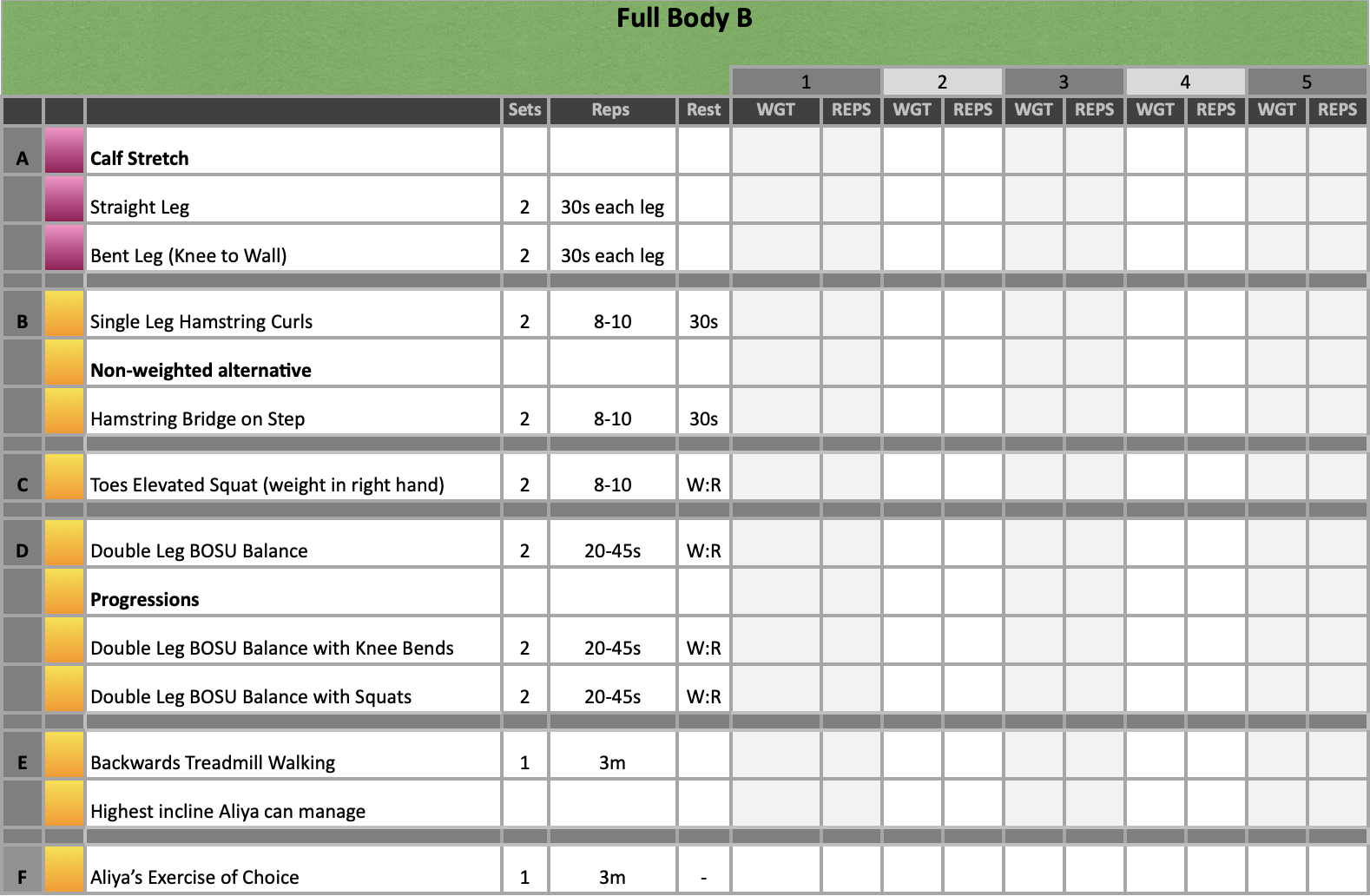

- Similar to the previous sessions, lots of single leg work was included in the sessions and led by the affected limb, i.e. right leg working weight was established and this was also used for the left. This time we really focused on slow and controlled movements on both limbs and trying to improve poor biomechanics. I was also able to include backwards walking into this training block which I reflected on previously as an exercise that is beneficial for balance and mobility.

- The biggest improvement in this training block were the participant successfully completing steps up with control and also keeping the heel down rather than remaining on tip-toes throughout the entire movement. When we first started with this exercise, she was reluctant to complete it at it caused pain and discomfort but we started with the smallest step we could find and slowly increased the height as she reported increased comfort with the movement.

- Other improvements, included improved postural stability and balance. The BOSU balance task initially was very challenging and poorly controlled. However, as this improved over time we then started to shift the focus onto an even distribution of weight through each leg and even shifting the weight from one side to the other. The participant also improved in her backwards walking. Both speed and ability to walk unsupported increased over the course of this programme and we even started adding additional tasks such as, touching her nose or closing her eyes to increase the difficulty. Finally, the participant had good eccentric control during leg extensions and squats in comparison to start of the programme. She was able to move in a slow and controlled manner without ‘collapsing’ at the most difficult portion of the movement.

What were you thinking and feeling?

- We were all happy with the progress that the patient was making; however, as the botox starting wear off it became difficult to keep the heel down again, particularly on squats. Even with the toes elevated, the calf complex length and tone would cause an elevation of the heel which was out of the patients control. As a result, the patients parents decided that wearing a splint during some of the exercises would be best. This was not something the patient was happy with so I focused on incorporating ‘free time’ where she could choose exercises she wanted to do, without her splint, to help maintain enjoyment in the rehabilitation experience.

What was good and bad about the experience?

- Increased session frequency and length provides more opportunity for repetition learning which helps to improve neuroplasticity.

- Noticeable improvements in her motor control show that the exercise are having a positive impact on function.

- Managing expectations. Naturally, the parents are really keen to do everything they can to help the patient improve. However, my concern is also the patients enjoyment of the sessions. If the entire session was completed in her splint this may keep her parents happy but she may become disinterested in her rehabilitation if she has no reprieve from this or a chance to engage with her programme and make some decisions herself.

Analysis

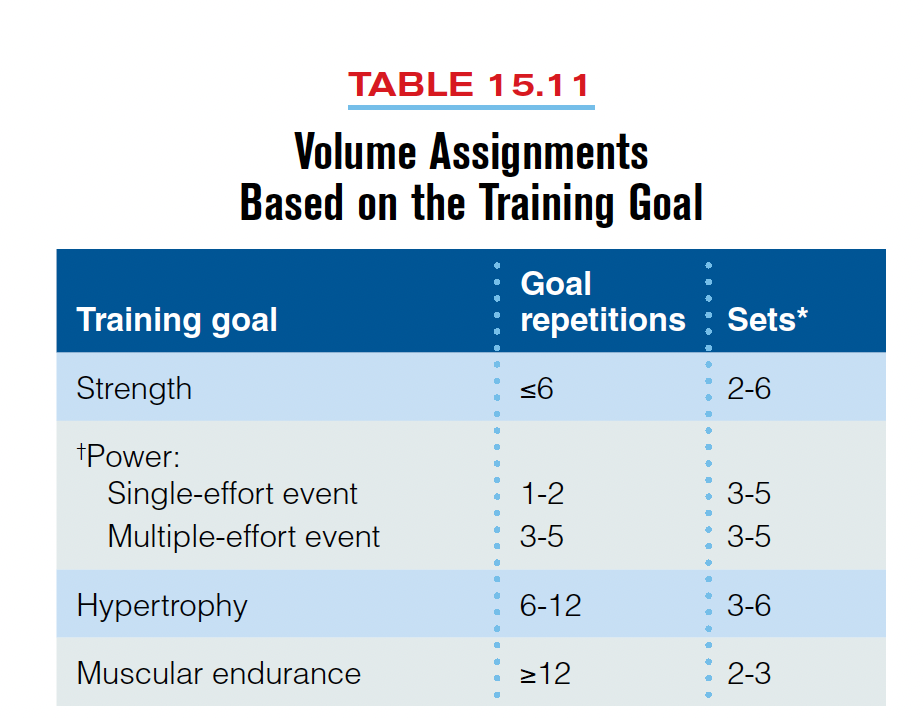

- Strength exercises were once believed to be contraindicated for children living with CP as it was thought to lead to increased spasticity (Gbonjubola, et al., 2021). However, this viewpoint has since changes and strength training programmes are considered a useful tool in the conservative management of CP alongside other forms of conventional exercise. As a result of this finding, I may look to change the patients rep range on certain exercises to work within a strength training block.

Table from Baechle and Earle (2008) – Essentials of strength training and conditioning. - In rehabilitation, we have been taught that whatever one side does, so does the other. This is to prevent deconditioning of the unaffected side. However, this is not an injury based scenario and I was starting to feel that even with 45 minutes at 2 sessions per week, we could be doing more by just looking at the unaffected side. However, I was unsure if this was a clinically sound approach. On further research, there is a rehabilitation technique called ‘constraint-induced movement therapy’. This is when the unaffected limb in restricted, forcing an individual to use the affected side. Therefore, my thoughts around focusing on just the right side seem valid in this instance. The type of therapy has been shown to be beneficial for function of the upper limb (Das & Ganesh, 2018). Therefore, it may also be worth including sole focus on the right upper extremity during the next phase too.

Conclusion

- Overall, the patient is making progress which is good to see. She is building confidence and rather than getting frustrated with challenging tasks she is starting to become competitive with herself. This then results in a sense of pride when completes something well and intrinsically motivates her to continue with her exercise.

- Using the splint in sessions may become a challenge; however, if I continue to ensure that there is enjoyment in her sessions this may help to negate some of negative emotional effects on the patient.

- The next phase will likely focus solely on the right side of the body to get the most out of sessions. However, I will need to consider fatiguability in doing this as she is likely to tire faster. Therefore, a reintroduction to upper limb exercises may help alleviate some of the fatigue I suspect the patient will experience.

Revisiting Reflection

References

- Baechle, T. R., Earle, R. W., & National Strength & Conditioning Association (U.S.). (2008). Essentials of strength training and conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics

- Das, S. P., & Ganesh, G. S. (2019). Evidence-based Approach to Physical Therapy in Cerebral Palsy. Indian journal of orthopaedics, 53(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_241_17

- Gbonjubola YT, Muhammad DG, & Elisha AT. (2021). Physiotherapy management of children with cerebral palsy. Adesh Univ J Med Sci Res 3, 64-8.