Monday 5th July 2021

Hours: 4 (Observational)

Patient presentations:

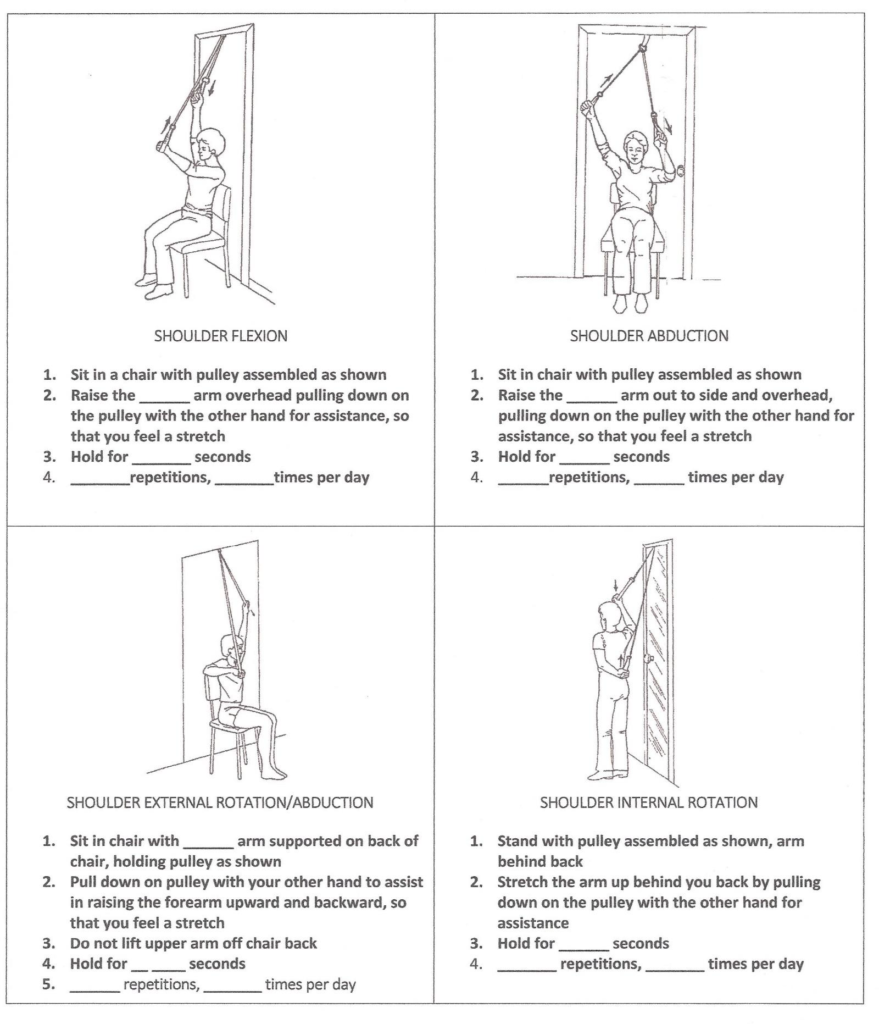

- Shoulder Revision

- Knee Replacement

- Capsular Release

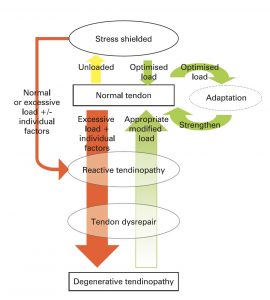

- Calcific Tendinitis

Reflection Focus

- Knee Replacement

Reflection Model

- The ERA cycle (Jasper, 2013)

Experience

- This patient was really struggling to adhere to her rehabilitation due to a period of ill health. She had kidney stones that resulted in a kidney infection; therefore, the patient was on antibiotics.

- The patient was fearful to do ‘too much’ much in the gym as she did not want to exacerbate her infection. As a result the physio focused on balance and stability exercises such as tandem stance balance.

Reflection

- This experience highlighted that things rarely ever go to plan and that your rehabilitation programme always needs to be flexible for the patient in front of you. Even though there are clear rehabilitation protocols for certain pathologies you cannot blindly apply the approach without knowing the patient in front of you. Furthermore set-backs during the rehabilitation process will not always be linked to the pathology itself; therefore it is important to get an understanding of a patient’s general health and wellbeing. This aligns with the teaching we have experienced, explicitly stating rehabilitation should be patient-centred.

Action

- When designing rehabilitation programmes I need to make sure I have simple progressions and regressions in place to adapt and adjust to any patient changes. Therefore, I will be mindful to include variations at the beginning of the programme design to be as prepared as possible.

Revisiting Reflection

- When starting the COVID-19 Rehabilitation Programme, I had to teach a group class to a variety of individuals of varying abilities. Therefore, I had to include progressions and regressions. All my COVID-19 exercise sessions have a suitable regression and progression. Furthermore, I will identify any issues or concerns during participant 1-1 phone calls and adjust further if necessary – see this session for an example of adapting to seated exercises.

References