6th December – 12th December

- Hours: 15

Main Theme Addressed During Phone Calls

- Fatigue as a catalyst for breathlessness and other ‘typical’ long covid symptoms.

- A number of participants this week noted that some of their ‘long COVID’ symptoms are worse on days where they feel particularly fatigued. For example, one participant notes that their breathlessness is more noticeable and another experiences heart palpitations. A 2021 study on long COVID symptoms noted that, ‘…in many [people] the breathlessness was an expression of fatigue, deconditioning and/ or breathing pattern disorders rather than the result of ongoing parenchymal lung pathology.’ (Taylor, et al., p.389). Naturally, if people have had a prolonged period of sedentary behaviour due to being ill with COVID-19 they may experience decreased muscle strength, reduced exercise capacity and MSK pain. (Demeco, et al., 2020). As a result, tasks that previously were deemed easy or tolerable by the participants can be much more fatiguing and exacerbate symptoms such as breathlessness. Therefore, one of the most important skills for participants to learn is correct pacing, planning and prioritising of daily and weekly tasks in order to reduce the likelihood of symptom flare-ups. Participants are currently using an activity diary to plan their days and weeks and those who have identified a link between their fatigue and ‘long COVID’ symptoms are now starting to adjust their weekly schedule to make tasks more manageable. I have also signposted participants to physiotherapy for BPD if they are struggling with breathlessness as it could also be a sign of disordered breathing patterns. This website has self help videos and also an information leaflet specifically for those suffering with breathlessness post-covid infection.

- Pacing physically involves slowing down.

- One participant had previously completed the HOPE programme – a programme aimed at helping individuals living with a chronic illness. She explained that the programme helped her to take control over her days by planning, pacing and prioritising effectively. However, the participant was still noting that her fatigue and breathlessness can be pronounced in the evenings/towards the end of the week. Furthermore, she still experiences breathlessness doing ‘small things’ around the house. On further questioning it appeared that the patient was pacing correctly For example, she breaks her work day into 2 x 3 hour working blocks and she takes rest periods after completing any task during her day. However, when I asked her how quickly she completes these small tasks she admitted that she tends to rush around when doing things.

- At this point I compared her goal of wanting reduced breathlessness and fatigue to someone running a marathon. Runners have different pacing strategies depending on what race they are running, i.e. a runner’s 5km pace will be much quicker than their marathon pace. If a runner attempted to complete a marathon at their 5km pace they would ‘burn out’ and not complete the race. The participant resonated with this analogy and iterated that she has been completing daily tasks too quickly. As a result she is burning out, which ultimately leads to increased breathlessness and fatigue. Therefore, over the next week the participant has agreed that she will view her days and weeks as a marathon and not a sprint. She notes that she is physically going to slow down when completing any task to see if this makes a difference to her symptoms.

GP Study Day 8th December

- Presented the COVID-19 Rehabilitation Programme to local GP’s.

- Aim = for GP’s to link up with the programme in order for them to refer patients.

- Outcome = GP’s happy to signpost patients; however, noted that self-referral is better for patient outcomes. Jokingly some of the GP’s passed a comment about self-referral is less admin for them. However, on a serious note they stated that they would much rather signpost patients to us as self-referral is better for patient outcomes. On further reading, I found this really comprehensive article on referral pathways for MSK conditions and the benefits are quite vast for both the patients and the healthcare system. I initially felt quite frustrated with the response by the GP’s as the aim was for them to provide us with clinical referrals. However, on reflection I can see why self-referral is not only a better option for themselves but for patients. In the grand scheme of things the NHS is under a lot of pressure post-pandemic and by having a referral system we will be alleviating time pressures GP’s face every day. Equally, self referral means that participants can be seen faster as opposed to waiting for the referral to be submitted and thus feel more satisfied with their care.

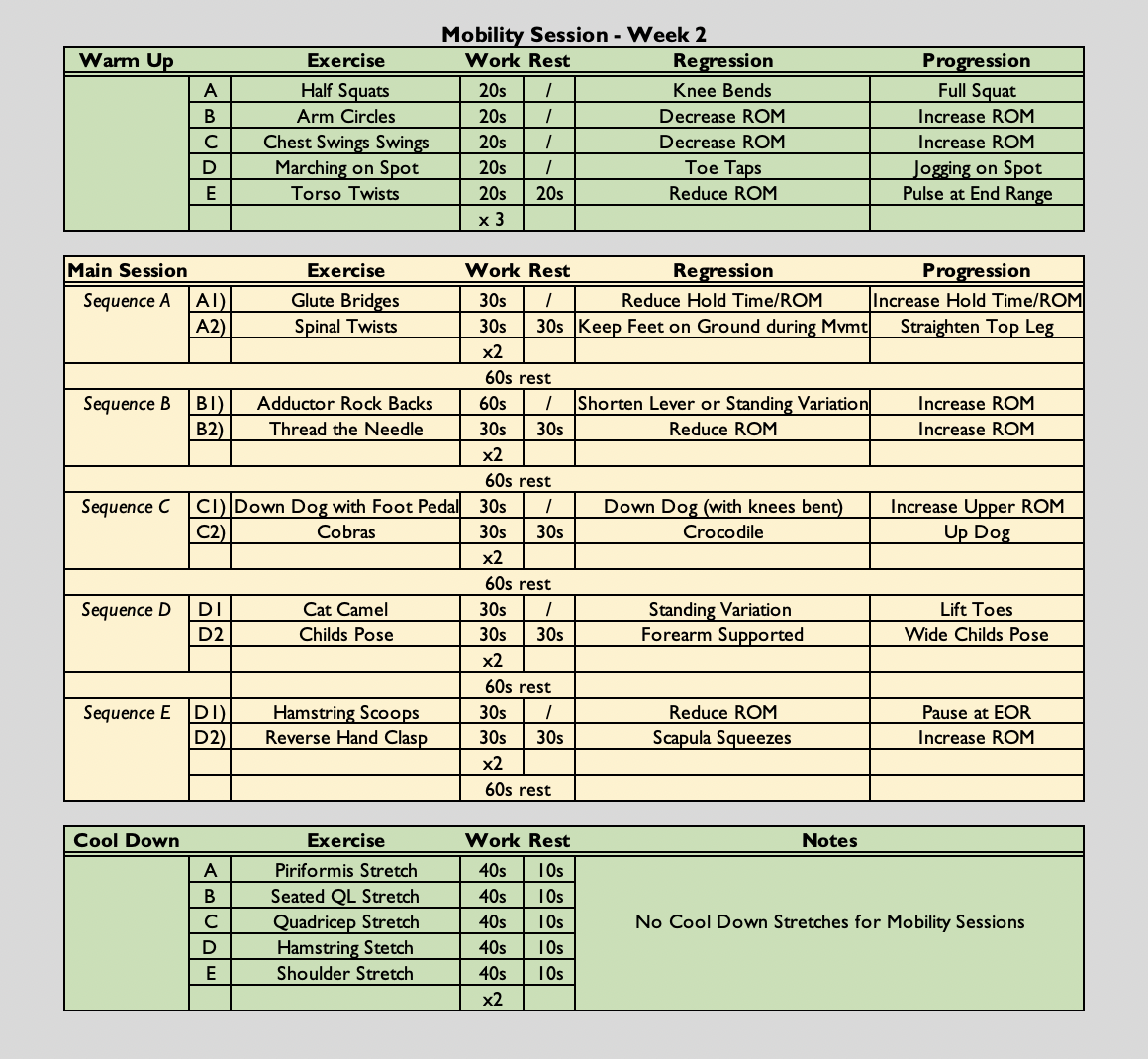

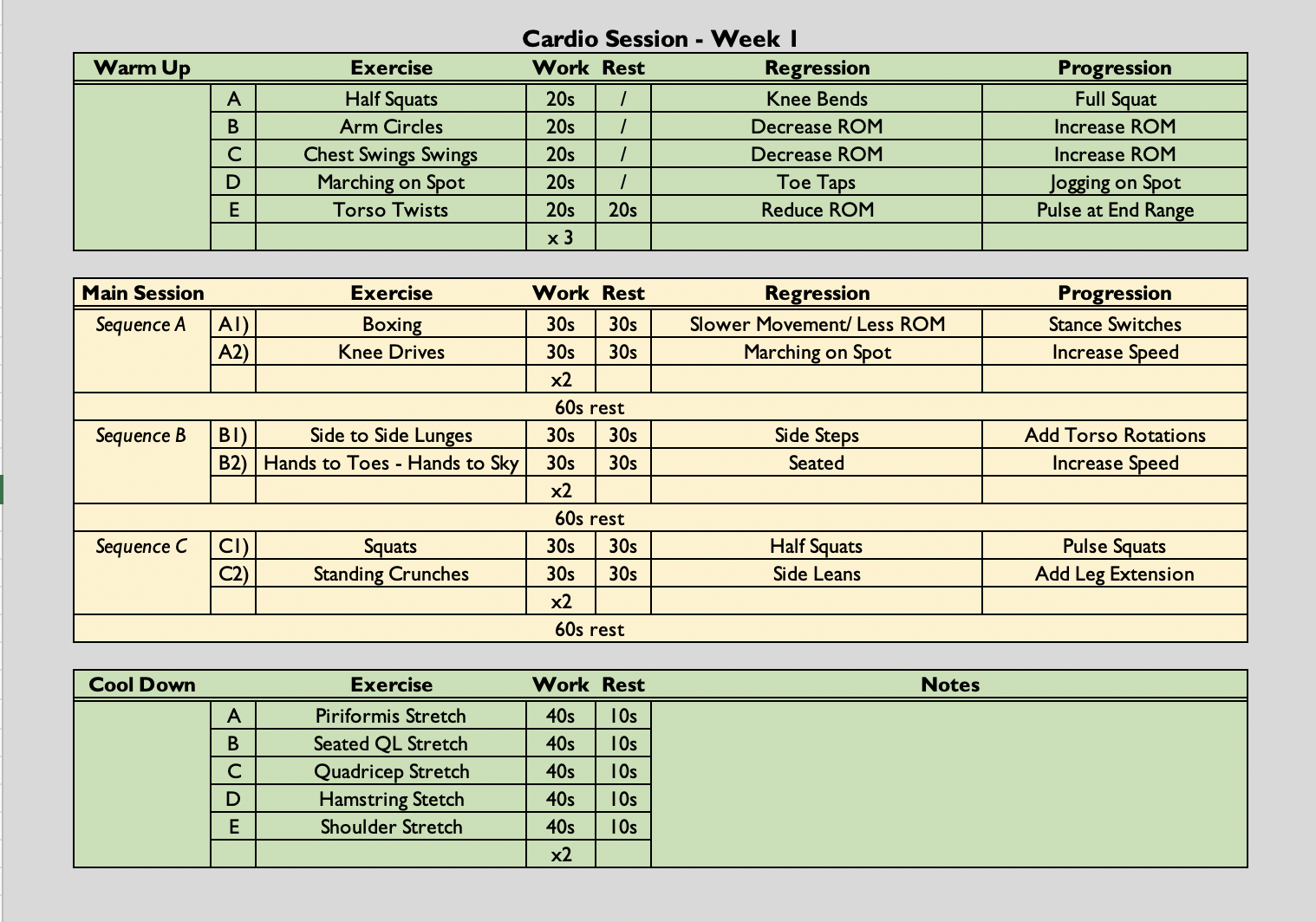

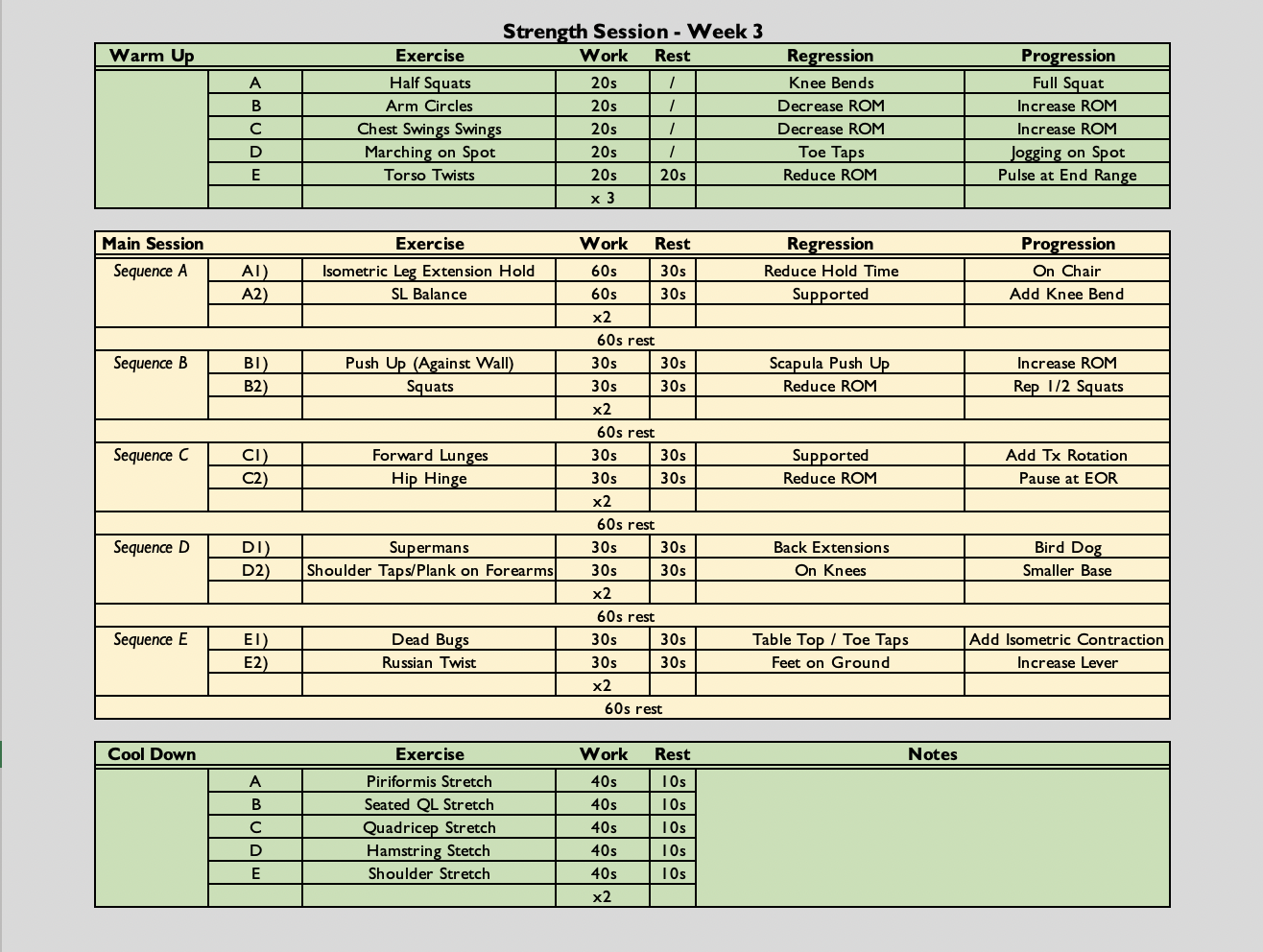

Strength Class

- (30 secs on (60 secs if singe leg), 30 seconds off (2:1) x 2, followed by a 60 second rest) x 5

- The class is always symptom-led as opposed to graded exercise therapy. Participants are free to rest when needed. They can end the class early if they have reached their limit and they can reduce the amount of sets they do if necessary.

Analysis & Evaluation

- This week has been a turning point for some participants.

- 3 participants have noticed improvements, physically and emotionally. Equally, those who have been struggling are starting to see what triggers their symptom flares and are beginning to make adjustments based on their findings. I also think I my patient communication is improving as I am finding different ways of explaining/coaching skills or tasks on a level that may be more relatable/understandable.

- However, 1 participant is experiencing symptoms that warrant further investigation – night sweats that are disrupting sleep and a circulation concern.

- This participant has experienced night terrors in the recent past which are reducing; however, his night sweats have not diminished and they are resulting in a broken nights sleep which will not be conducive to managing fatigue. He also reported that his feet and ankles are swollen. I followed the NHS advice on oedema and encouraged the participant to book an appointment with his GP if it does not settle, gets worse or he develops any symptoms identified on the NHS website as emergent.

- I feel like I handled this situation well by firstly checking for any signs and symptoms of a DVT and other red flags. Equally, night terrors and night sweats are likely outside of my scope of practice. Night sweats combined with night terrors could be a sign of more complex EWB needs, such as PTSD (Jimeno-Almazán., et al. 2021). PTSD is something that would require specialised support that is not offered within this programme.

Conclusion

- Next week I will be following up the results from the participant who will be adjusting her pacing strategy. I am hoping that she will report increased energy levels and reduced fatigue. I will also be following up with the participant who I have asked to get in touch with his GP. However, I am aware that it is currently quite difficult to ascertain an appointment with a GP if not emergent. Therefore, next week I will also be ensuring the participant is accessing the EWB content of the programme too.

Revisiting Reflection

- The participant who was adjusting her pacing strategy made some real progress over the week. She explained, she was able to get much more done and although having to consciously think about slowing down it has helped her enjoy tasks that she previously felt too tired to do e.g. Horse riding.

- The participant who I suggested should put and e-consult in has yet to do so but there has been no improvement in his symptoms. His night terrors and nights sweat have stopped which has resulted in better sleep. Therefore, the participant notes his fatigue is substantially less. The participant has stated he will put an e-consult in this week so I will need to continue to follow up on this.

References

- Jimeno-Almazán, A., Pallarés, J. G., Buendía-Romero, Á., Martínez-Cava, A., Franco-López, F., Sánchez-Alcaraz Martínez, B. J., Bernal-Morel, E., & Courel-Ibáñez, J. (2021). Post-COVID-19 Syndrome and the Potential Benefits of Exercise. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(10), 5329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105329.

- Demeco, A., Marotta, N., Barletta, M., Pino, I., Marinaro, C., Petraroli, A., Moggio, L., & Ammendolia, A. (2020). Rehabilitation of patients post-COVID-19 infection: a literature review. The Journal of international medical research, 48(8), 300060520948382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060520948382