7th February – 13th February

- Hours: 15

Main Theme Addressed During Phone Calls

- Thoughts and feelings around continuing with their rehabilitation independently.

- How was the programme helped each participant individually.

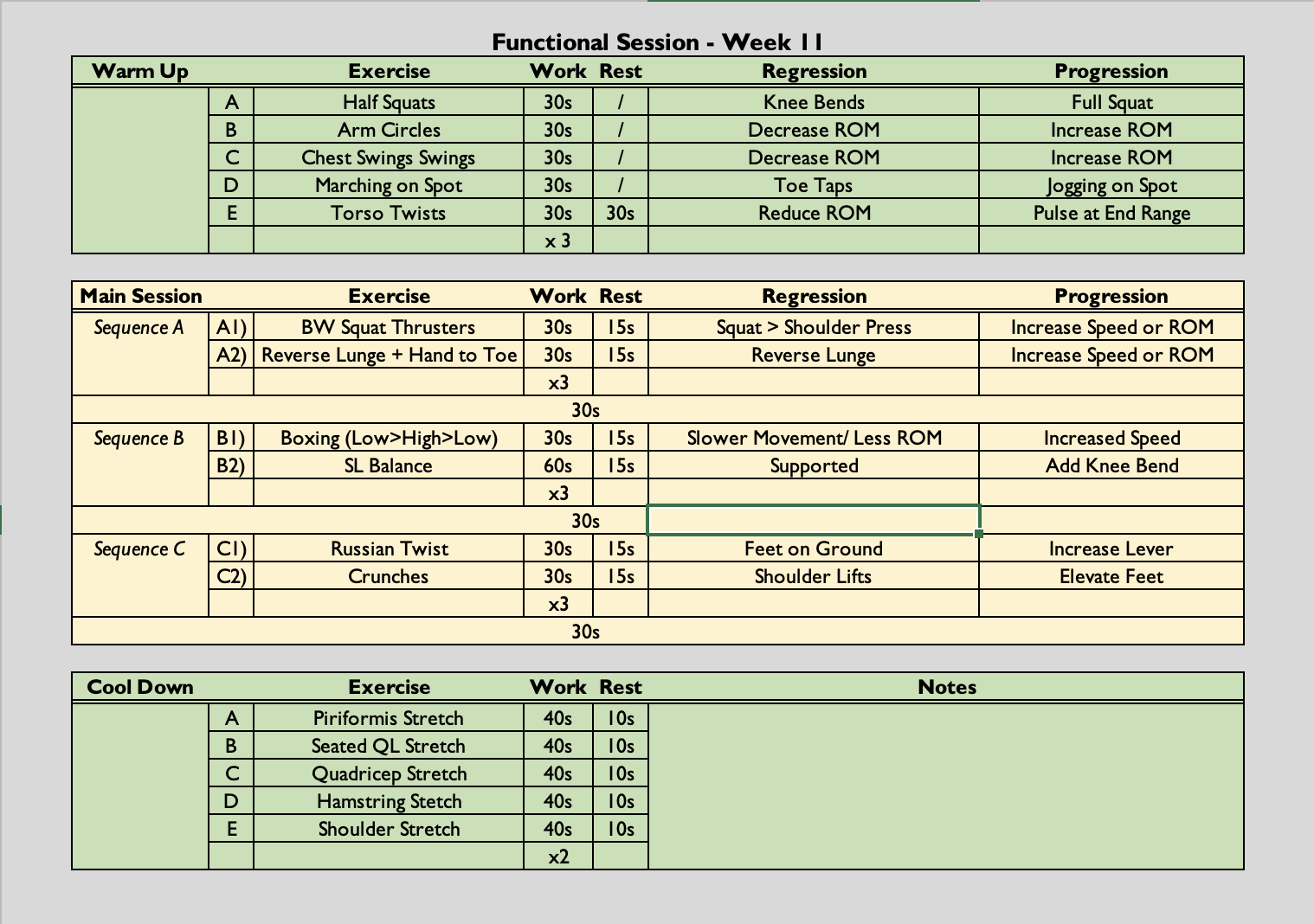

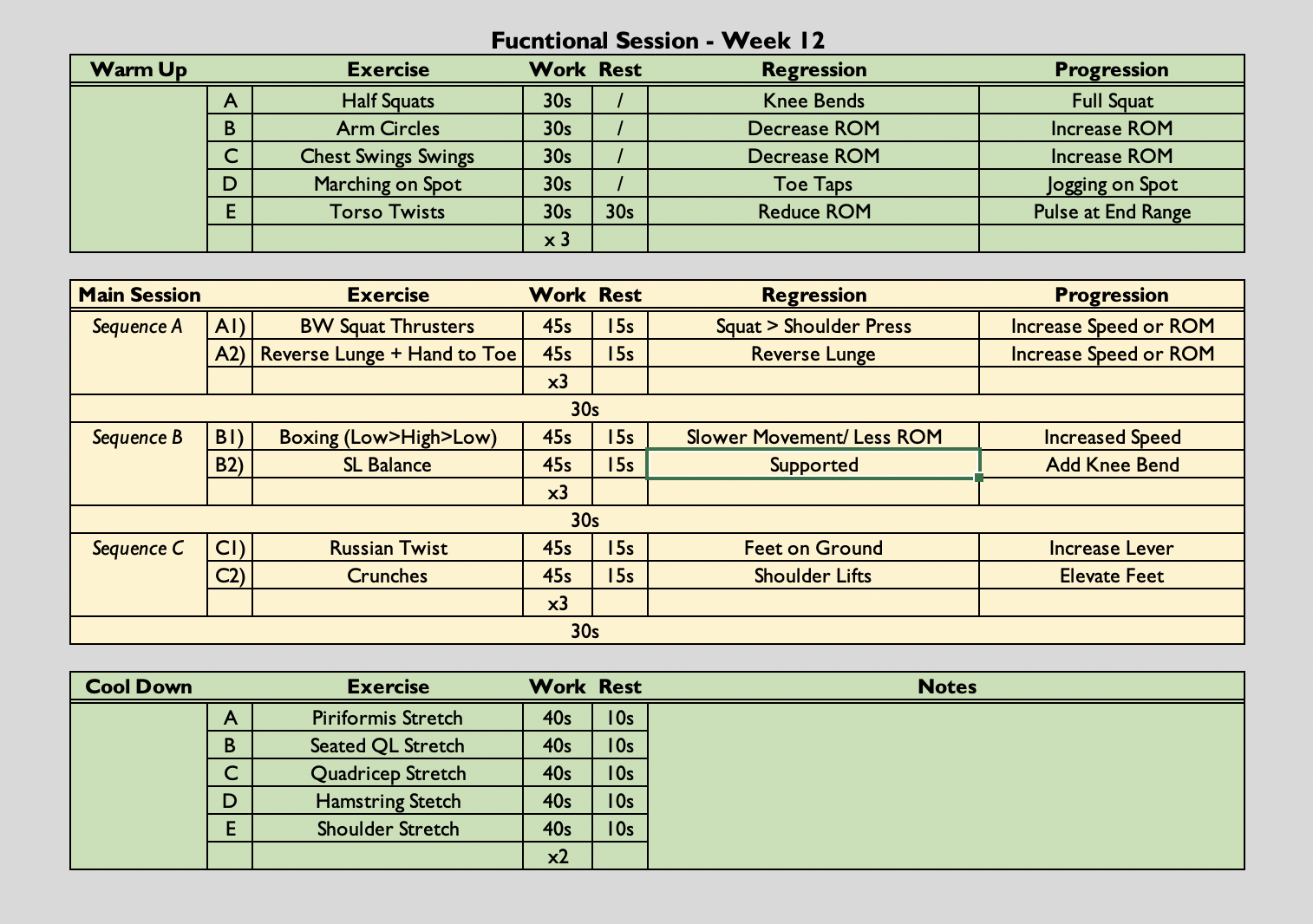

Functional Exercise Class

- ((45s x 15s rest) x 3 followed by a 30 second rest) x 3

- The class is always symptom-led as opposed to graded exercise therapy. Participants are free to rest when needed. They can end the class early if they have reached their limit and they can reduce the amount of sets they do if necessary.

- Increase of 15 seconds during working phase due to familiarity of new exercises.

Drop-in Session

- Once again, this was a fairly hands-off session in terms of guidance from me. All participants were happy with their training and looked confident doing so. They required no prompting from me which indicates that they would be capable of continuing their training sessions without guided support.

Analysis & Evaluation

- All participants, excluding one, reported improvements since starting the programme. Improvements noted were; improved energy levels, reduced fatigue, improved sense of wellbeing, decreased breathlessness and an increased exercise capacity.

- Many reported that it was having a group of people going through something very similar to them that helped their recovery. They felt they were surrounded by people who understood what they were going through and that it was nice to be on a programme where people didn’t just think they were ‘making up’ their symptoms.

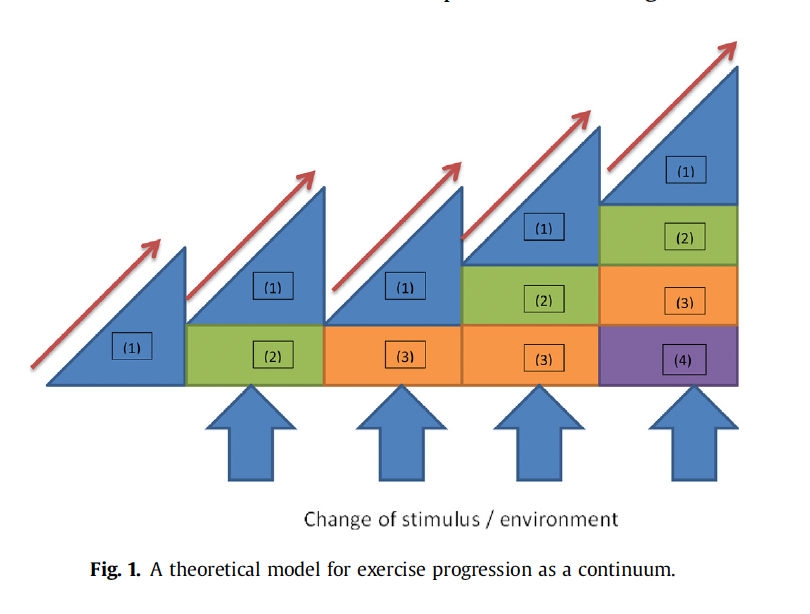

- One participant ran 5k the weekend before our final week and he was delighted. One of his goals was to return to running but he never expected to be this far along already. At the very beginning of the programme this participant was completing 1 mile walks and suffering from fatigue on a daily basis. We focused on the 10% rule with his walks and only increased his walking distance or time if he felt he was able to, in accordance with his fatigue. When we reintroduced running, which was only a few weeks ago, we looked at doing 30 secs of running to 90 secs of walking. This worked well and then participant was then happy to control his pacing from this point onwards. To have run a continuous 5k at this stage does seem like a steep increase and it is more than likely his incremental adjustments were too large. However, the participant noted that there were no ill effects after the run so we could have potentially been erring on the side of caution previously.

- Interestingly, the patient above seems to have made a spontaneous recovery. He is also not the first one I have seen do so. There has been a handful of participants that I have worked with over the past year who at any stage during their recovery seem to make such a steep improvement in such a short space of time that they appear to have improved overnight. Very little is still known about long covid and why some people make fast recoveries than other is still unknown. However, it is known that the more symptoms you present with during the acute infection the more likely you are to develop long covid (Sudre, et al., 2021). Furthermore, being over the age of 50 and having pre-existing health conditions – mental of physical -increased the risk of developing long covid (Crook, et al., 2021). Therefore, maybe having less of these risk factors may contribute to faster or even spontaneous recovery if the correct strategies, such as pacing, are put in place to allow optimal healing.

Conclusion

- It has been a great challenge to work with people experiencing symptoms of long covid. It doesn’t exactly fit in with what we have been learning but there is an overlap in the knowledges and skills. For example, I have been able to use my exercise knowledge to create appropriate activities for the group and individuals. However, I have probably learned more from the experience than what I took to it. I think before the rehab programme I didn’t really consider psychosocial factors as important. This is likely because learning anatomy, pathologies and rehabilitation was such a challenge to me that I prioritised it over the psychology of rehabilitation. However, I have learned that this can be such a determining factor to successful rehabilitation. If a person doesn’t believe what you or they are doing will help them, then they are less likely to adhere and/or see positive results.

- Moving forward, with all my rehab, I will be working with patients to explain the benefits and the underpinnings of treatment so they fully understand why they are doing or receiving a certain course of treatment.

Revisiting Reflection

- Crook, H., Raza, S., Nowell, J., Young, M., & Edison, P. (2021). Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 374, n1648. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1648