13th December – 19th December

- Hours: 15

Main Theme Addressed During Phone Calls

- Two participants are really struggling with fatigue.

- One participant is a busy mum who works full time. She believes she went back to work too soon; however, she cannot take any time off as that will result in financial difficulties and/or stress. This participant is up early in the morning, around 5am, to take her child to her sports training. She then works full-time (predominantly desk- based job) before taking her child to exercise training in the evening. When she gets home in the evening she cooks and cleans for the family before going to bed.

- When we discussed how to make small changes to make her life easier and assist with pacing, planning and prioritising her energy expenditure, (e.g. taking the bus to work, using the elevator instead of taking the stairs, delegating household tasks etc) I was met with some resistance from the participant. She felt that she couldn’t delegate household tasks as this wouldn’t be fair on her teenage daughter and she didn’t want to take the bus to work because she wanted to improve her CV fitness.

- I tend to have quite a gentle manner when suggesting changes participants could make to help manage their fatigue; however this participant was not taking on any of the suggestions nor reflecting on how she could make changes to help support her recovery. So, in this instance, I changed my approach to be a bit more direct. I explained to her that, even though she has good intentions, what she is currently doing is not improving her symptoms and as a result something needs to change. This prompted an emotional response from the participant as she expressed feeling unhappy in her work and always ‘clock watching’ as she always has somewhere to be. She agreed that she wasn’t putting herself first and therefore, not getting better. I left the participant with a task this week – to write down all of her non-negotaible tasks and a way in which she can make them easier for herself, reiterating the examples I expressed on the phone call earlier. The participant agreed that this was a good idea.

- The second participant is off-sick from work as a physiotherapist and describes her only ‘non-negotiable’ of the day as walking her dog. The conversation wasn’t too dissimilar to the one above as this participant was agreeing to social events that she knew were going to exacerbate her fatigue. She admitted she was agreeing to them because she felt like she would be letting people down otherwise. I gave this participant a similar task to the one above . Before agreeing to something that is a non-negotiable ask yourself, ‘will this help my recovery today?’ The participant really resonated with this and expressed that she needs to put herself and her recovery first more often.

- One participant advised to complete exercises seated.

- Exercise induced a coughing fit for this individual on the very first session. Following from this the participant had been too unwell to participate in the programme and hadn’t exercised since. The participant expressed that she was now ‘on the mend’ and wanting to attend the strength class. To regress exercises even further for this participant I offered seated variations for all exercises. Although not happy to be restricted to seated exercises the participant understood why and agreed to start gentle to avoid a relapse.

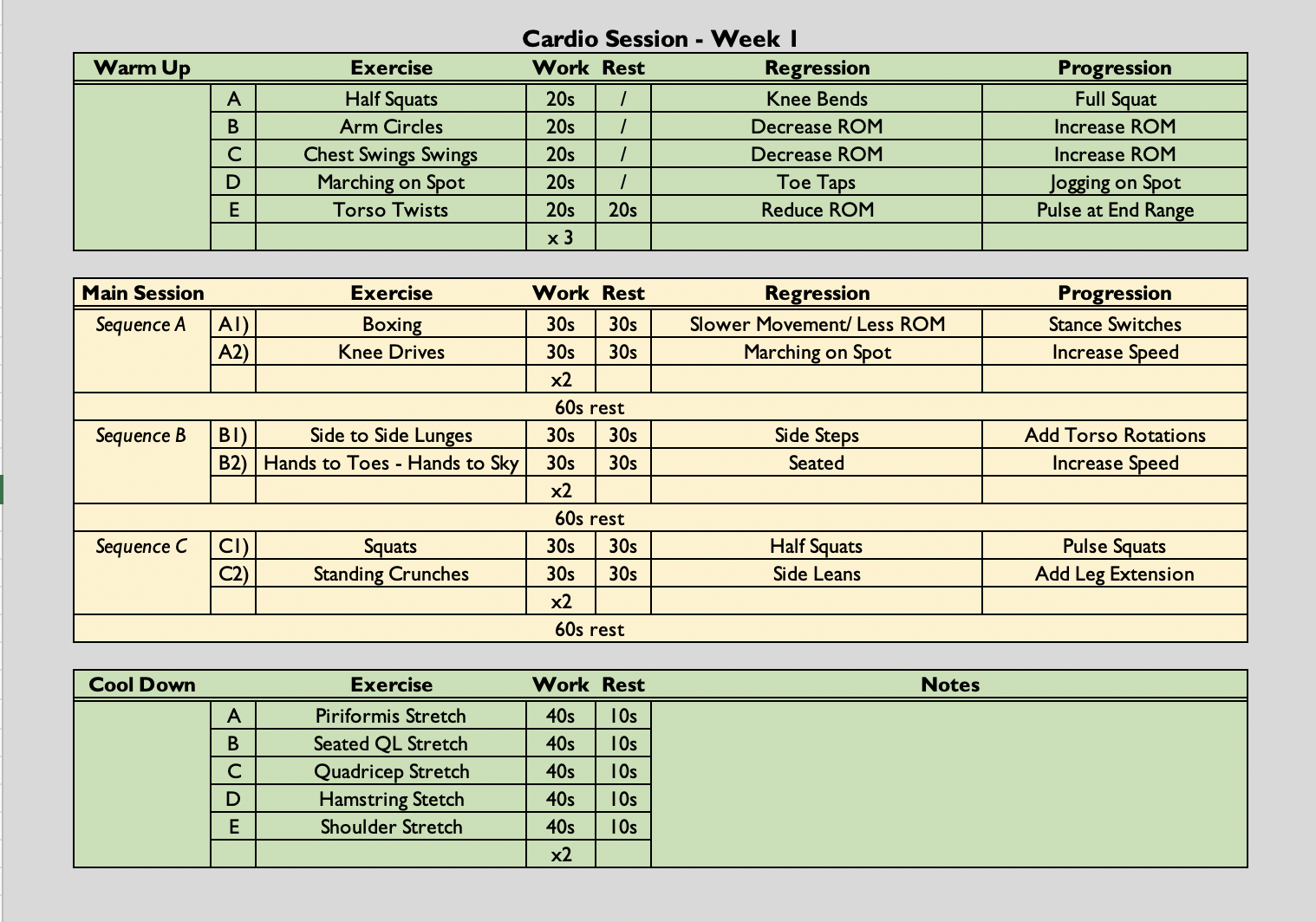

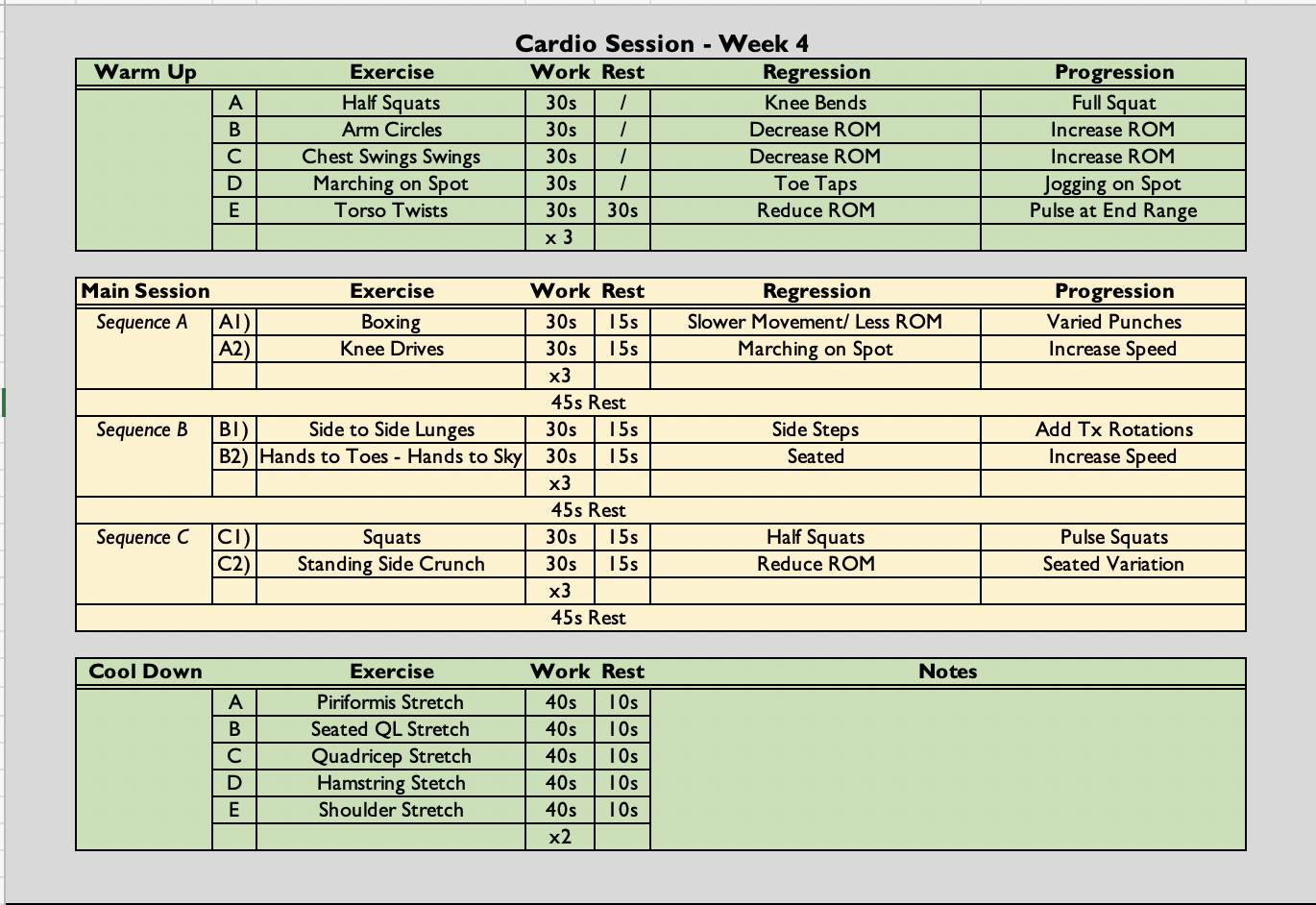

Cardio Class

- (30 secs on, 15 seconds off (2:1) x 3, followed by a 45 second rest) x 3

- The class is always symptom-led as opposed to graded exercise therapy. Participants are free to rest when needed. They can end the class early if they have reached their limit and they can reduce the amount of sets they do if necessary.

Analysis & Evaluation

- My coaching was very clear and concise throughout the class despite having a number of variations to demonstrate throughout. Equally, I ensured when offering variations they were not direct in the group setting to avoid any negative associations with being singled-out. As I had already spoke to the participant who needed the seated variations there was no need for me to draw attention to the regression being added for her sake.

- It was good to see the participants who are really struggling with fatigue recognise that something needs to change in order for them to see improvements. These conversations made me realise that sometimes a more direct approach is needed when it comes to offering help and support. However, I know if I tried this approach in earlier weeks, before a rapport had been established, it may have been received poorly by the participants and may not have had the same reflective impact I wanted it to.

Conclusion

- On reflection, I think some of the advice I give is very passive. This week I gave advice in an active way which meant that the participants had to think about what they could change rather than rely on me for suggestions. By not being actively involved in suggestions for their own rehabilitation, participants may not reflect and/or learn during the process. Huang and Wang (2021) suggest that reflection and learning should be part of the recovery process for injured athletes. Therefore, I am going to make more of a conscious effort to pose questions and actively engage participants in taking control of their own recovery rather than becoming overly reliant on external support from myself. Hopefully, the process of learning and reflection will equip them with the confidence to maintain their rehabilitation long after the programme ends.

Revisiting Reflection

References

- Xiang Huang, Xiaoping Wang, “Influencing Factors of Athletes’ Injury Rehabilitation from the Perspective of Internal Environment“, Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, vol. 2021, Article ID 2368847, 7 pages, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2368847