Monday 7th June 2021

Hours: 4 (Observational)

Patient presentations:

- Total Hip Replacement

- Subacromial Decrompression

- Lumbar Decompression

- Sciatica

Reflection Focus

- Sciatica

Reflection Model

- The ERA cycle (Jasper, 2013)

Experience

- Patient was experiencing pain in the knee which referred down into her toe. However, on this visit this referred pain had ceased and was in the knee only.

- The clinician took the time to educate the patient on the behaviour of nerve pain and reassured her that the reduction in referred pain was a sign of improvement.

- The clinician did not change the exercise prescription for this patient.

Reflection

- I felt a bit confused on this case as the patient wasn’t complaining of any lower back pain which I had previously thought was a pre-requisite for suspected sciatica. However, on further reading LBP may or may not be present in someone who has sciatica and, if they do, it is likely to be less severe than the referred leg pain (Koes. 2007; Konstantinou. 2012). Furthermore, pain that radiates below the knee is considered an indicator for sciatica.

- This aligns with messages that have been taught to us about imaging. E.g. If you imaged 100 people without LBP a number of these could, for example, have a discongenic pathology but be asymptomatic.

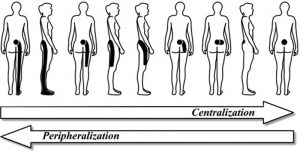

- The patient’s pain in this instance was centralising which is when the pain moves closer towards the spine (Albert. 2012). As the clinician stated to the patient, this is an indicator of a positive outcome. Peripheralisation on the other hand would indicate that the condition had worsened.

Action

- I was clearly misinformed about how sciatica can present itself. Reflecting on this further, I clearly have some assumptions about LBP that need to be addressed. Therefore, I need to look into the possible presentations of sciatica and treatment strategies.

Revisiting Reflection

- The NHS summarise sciatica as lower extremity pain and/or altered sensations with or without back pain. It has useful conservative management strategies and when to be concerned – cauda equina red flags. The most common cause of sciatica is a ‘slipped disc’ but equally an injury to the back or spinal conditions such and spondylolisthesis and spinal stenosis could be the underlying reason behind sciatic nerve irritation. Due to there being many different causes of sciatica it is really important to take a thorough subjective history, align them with patient characteristics (such as age, lifestyle, previous trauma, etc.) to determine the correct cause of treatment or if an onward referral may be required. For example, if I suspected a disc protrusion repeat extensions may be a beneficial prescription to alleviate symptoms.

References

- Koes, B. W., van Tulder, M. W., & Peul, W. C. (2007). Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 334(7607), 1313–1317. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39223.428495.BE

- Albert, H. B., Hauge, E., & Manniche, C. (2012). Centralization in patients with sciatica: are pain responses to repeated movement and positioning associated with outcome or types of disc lesions?. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society, 21(4), 630–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-011-2018-9

- Konstantinou, K., Lewis, M., & Dunn, K. M. (2012). Agreement of self-reported items and clinically assessed nerve root involvement (or sciatica) in a primary care setting. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society, 21(11), 2306–2315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-012-2398-5